By Rehana Thowfeek

Originally appeared on Groundviews

Photo courtesy of EFE

By all estimates, Sri Lanka’s economy is expected to grow around 1.5% in 2024, making inroads into reversing the economic contraction the country experienced since 2020. Sri Lankan authorities have reached a staff level agreement with the IMF earlier this month and, pending executive board approval, Sri Lanka will receive the second tranche of $330 million soon.

Sri Lanka’s reserve position has improved somewhat from the record low levels it was once at – there are $3.5 million currently in reserves, which is sufficient to cover 2.6 months worth of imports, albeit still a worrisome situation. Tourism earnings and worker remittances are picking up and the cumulative trade deficit has narrowed in comparison to last year. Inflation is tapering at 0.8% in September (the base year has been revised to 2021), the result of the tight monetary policy stance taken by the Central Bank since April 2022.

Import restrictions brought in response to the dwindling foreign reserves are now being phased out with all but a few items still restricted. Due to the rapid decline in purchasing power experienced by the people in the past year, demand for imports may remain subdued but maybe offset by more favorable credit conditions. Policy rates have been further reduced and due to more favorable economic conditions banks are now showing greater willingness to lend in comparison to 2022, which bodes well for business revival.

The ability of Sri Lanka’s economy to redeem itself and firmly place itself on a path of inclusive and sustainable growth lies in how successfully the country can execute the necessary economic and governance reforms. Debt restructuring will ease the burden of external debt repayments in the medium term but eventually Sri Lanka will have to start servicing its external debts once again.

If Sri Lanka does not manage to adequately grow its economy to accommodate these payments with sufficient tax revenues and export earnings, the country risks slipping back into a situation similar to that experienced in 2021 and early 2022. The global situation is not favorable for economic recovery with many large economies undergoing recession and multiple wars being fought on different fronts.

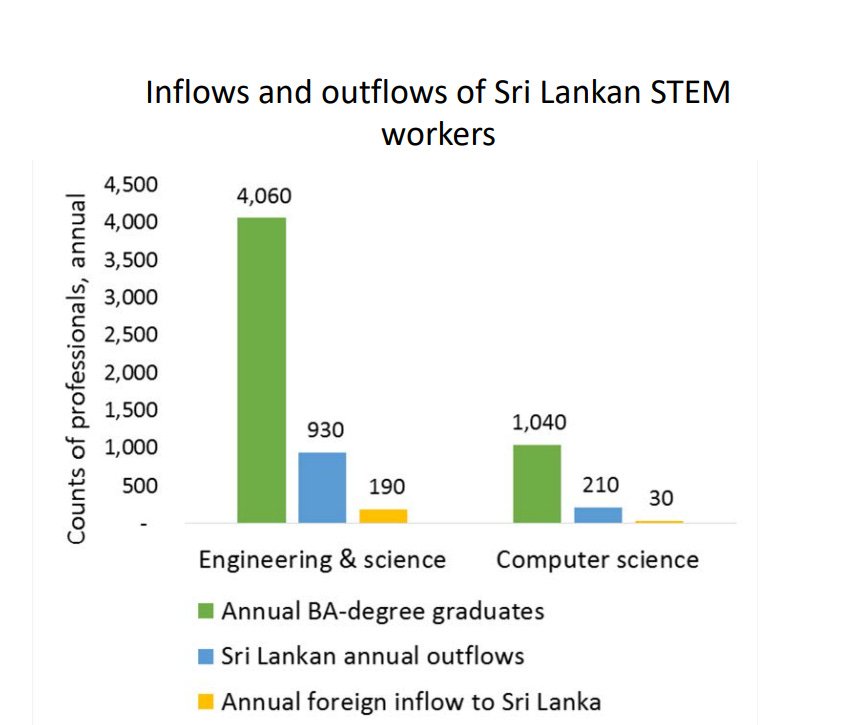

The tourism industry shows signs of recovery but can be impeded by the labor migration. The tourism industry already faced issues with attracting labor, as it is not seen as an attractive or well-paying industry to work in. With workers either having left the industry to join other industries in the wake of the Easter attacks and the Covid impact or migrating to other countries due to the crisis, the industry will struggle to cater to the demand that it once managed to.

This calls for exploring the possibility of opening up the borders for foreign labor to work in Sri Lanka, which is a controversial issue to say the least. With mass migration, the country’s health sector is also in a bad state but opening up this sector to foreign labor is even more controversial than it would be to the tourism sector.

The importance of governance reforms cannot be overstated; addressing the governance failures that precipitated Sri Lanka’s economic decline over the past few decades is the only way to prevent reneging back into bad policy making. Checks and balances are important for a well-functioning economy and society. Since pockets have grown fat and powerful with lax governance structures for many decades, dismantling these systems that work in favor of a few and shaping them to work in favor of many is a difficult endeavor in the best of time.

Reforms to state owned enterprises are in the works, albeit at a slow pace. There are plans to pass the necessary laws to divest State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and to set up a holding company to manage whatever SOEs remain. Reforms to SOE behemoths like the Ceylon Electricity Board are being tackled separately. The country’s flagship poverty program, Samurdhi, is being rehauled into a consolidated welfare program called Aswesuma with better targeting mechanisms, better entry criteria and exit clauses to make the program more effective. The new program also attempts to depoliticize welfare which hindered the effective function of its predecessor.

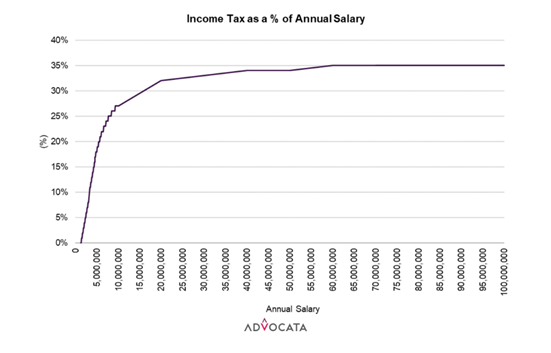

The budget, which can effectively signal the incumbent government’s commitment to reforms, is already off to a bad start. The government announced that public sector salaries would be increased. With no access to printed money from the Central Bank since the enactment of the new Central Bank Act nor access to foreign loans, the government has decided to increase VAT, perhaps to fund these salary increments.

The incumbent government has made no attempt to cut public sector expenditure and has instead opted to further increase its salary bill, which already swallows up a massive share of the tax revenue – 65% in 2022. This number is even higher when you add in the pensions bill. The government has fallen short of IMF targets on tax revenues in the recent review, so increasing expenditure further, especially just to pacify public sector workers in the light of elections, is utterly imprudent in the context.

Continuing to burden the general public with taxes to fund frivolous, unbridled expenses with no meaningful reform of public expenditure would serve as a harsh reminder to the people of Sri Lanka that the system change once demanded by the sea at Galle Face is yet to be seen, precipitating another wave of civil unrest.

It is not an understatement to say that the precarious stability that has been achieved hangs in the balance, and now with a looming election, the precarity worsens. There is no political consensus on the way forward which can solidify the reforms that the country ought to take – every possible reform is contested which does not bode well for the economy. The jostle is between the NPP, SJB, SLPP+UNP and other possible wildcards such as Dilith Jayaweera and Dhammika Perera, all of whom propose varying economic policies.

The resolution lies in a concerted effort towards comprehensive economic and governance reforms, fiscal prudence and a unified political will that transcends party divisions. The critical choices ahead will determine whether Sri Lanka can chart a stable, inclusive and sustainable economic course or succumb to the persistent vulnerabilities that always threaten its progress.