Originally appeared on Daily FT

By Roshan Perera, Thashikala Mendis, and Janani Wanigaratne

The second tranche of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Extended Fund Facility (EFF) was delayed as the country failed to meet some of the program targets including the Government revenue target. This prompted the IMF in their latest review to reiterate the need to “strengthen tax administration, remove tax exemptions, and actively eliminate tax evasion” to ensure revenue is collected as per the program targets. This requires intense efforts by the Government if the country is to achieve sustainable macroeconomic stability.

Corporate Income Tax (CIT) in Sri Lanka has the potential to significantly contribute to Government revenue. However, CIT performance has been dismal with collection averaging around 1% of GDP over the last two decades although economic growth averaged around 4% during the corresponding period. It peaked at 1.9% in 2022 due to some one-off taxes.1 Compared to other countries in the region as well, CIT collection in Sri Lanka has been abysmally low (see Figure 1).

Further, CIT collection is concentrated in a few sectors in the economy. The 230 companies listed in the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) for financial year 2019/20 account for around 25% of total corporate income tax collection. However, financial services, food & beverages, and telecommunications account for a disproportionate share of taxes (see Figure 2). Sectors such as wholesale and retail trade, real estate and transportation which account for more than 25% of GDP, contribute less than 2% in CIT. Tax holidays and concessionary tax rates to selected sectors have eroded the CIT tax base, leading to lower CIT revenue collection. Ad hoc tax concessions complicate tax administration, distort resource allocation and provide opportunities for rent seeking and corruption.

Tax incentives

With the liberalisation of the economy in 1977 and the shift to a more export oriented development strategy, the Government sought to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) by offering attractive tax incentives, first under the GCEC Act No. 4 of 1978 and subsequently the Board of Investment (BOI) of Sri Lanka from 1992. Tax incentives were also offered under the Inland Revenue Act. The enactment of the Strategic Development Projects (SDP) Act, No. 14 of 2008 permitted the Minister in charge of investment the discretion to grant incentives to projects deemed of strategic importance with only subsequent ratification by Cabinet and Parliament.

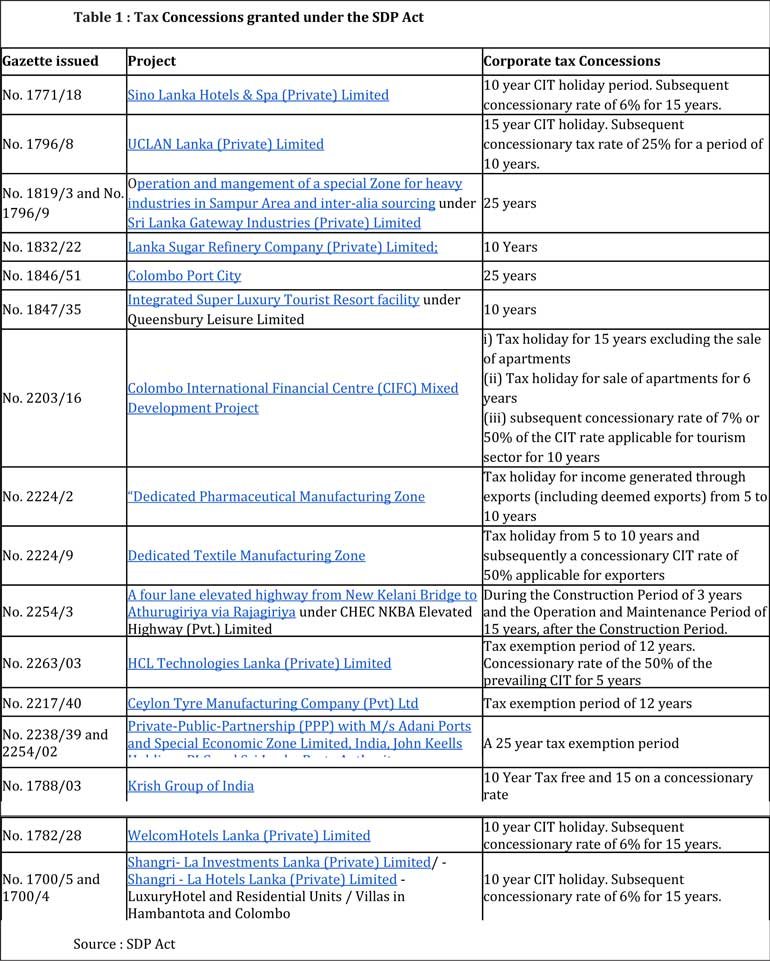

The lack of clear criteria of what constitutes a “strategic development project” in the SDP Act and the discretion given to the Minister to decide on what constituted a “strategic” project led to generous tax holidays and incentives granted to projects that were not in any sense strategic (see Table 1 for a list of projects granted under the SDP Act). Furthermore, tax concessions under the Act have been awarded to projects that are not purely foreign funded, violating one of the core objectives of this Act, which is to attract foreign investment.

The operation of multiple tax jurisdictions has led to an overlap of tax incentives, obscuring the process of monitoring the overall benefits and costs of tax incentives provided. Lack of transparency and well-defined criteria as well as poor evaluation of projects has led to the granting of tax incentives without proper justification, leading to large revenue losses.

Transparency, availability and accessibility of information regarding companies that have received tax incentives, especially under the BOI Act, are limited3. In light of this, the IMF diagnostic report has highlighted the need for a more transparent data sharing protocol.

The case of Port City

More recently the Colombo Port City Economic Commission Act, No. 11 of 2021 was given the authority to grant tax incentives within the Port City.

The CPC Act grants incentives to businesses that are identified as strategically important. Extraordinary Gazette 2343/604 lists several industries as strategically important. Even though the Act provides a descriptive definition of a business of strategic importance, the rationalisation for these industries to be selected for special incentives is unclear. Especially as some of these industries already exist in Sri Lanka, which puts them at a disadvantage. Moreover, under section (4) subregulation (3) of the Extraordinary gazette 2343/60, one of the criteria for granting incentives is the ability of the business to demonstrate to the Port City Commission the potential contribution to Sri Lanka’s economy and social development by fostering innovation, knowledge transfer, technology transfer, research and development. This criteria is vague and subjective, thus allowing the Commission to grant incentives at its discretion.

Granting incentives often leads to differential tax treatment creating an unlevel playing field. While an entity in an already established industry within the country located within the CPC is provided generous tax incentives, the firm located outside is subject to the normal taxes operating in the rest of the country. Such differential treatment could create labour market distortions, as the employees in the Port City benefit from tax exemptions.

Sri Lanka has not been able to attract Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) despite the plethora of incentives offered. It is questionable whether we can expect different results by applying the same failed strategy with the Colombo Port City. For instance, out of 74 land plots, only 6 were leased so far, and even those have not yet materialised.

To improve the performance of CIT, reforming the existing incentive structure is critical.

Improving investment environment

Evidence suggests that tax incentives are not the most important factor attracting FDI. Rather investors prioritise factors such as macroeconomic stability, access to skilled labour, and quality infrastructure facilities when making investment decisions. Therefore, shifting focus from relying on tax incentives to creating a favourable macroeconomic environment and policy consistency while providing the necessary resources and infrastructure will be more important to attracting investments. This will reduce distortions in the economy while ensuring the Government’s revenue base is protected.

Renegotiating tax incentives

Given the weak fiscal position of the country and the debt restructuring exercise being carried out at present, a similar exercise to renegotiate existing tax incentives may be warranted. Rationalising existing tax incentives would widen the tax base and enable lowering corporate tax rates.

Centralising tax incentives

If tax incentives are to be granted it should be done by a centralised authority. This authority should be able provide justification for granting special tax incentives by carrying out a cost benefit analysis. Clear objectives and proper criteria for granting incentives should be established and the authority held accountable for monitoring the progress of the investments to ensure the objectives of the investment are fulfilled. Failure to meet the objectives should lead to an immediate cancellation of the incentives granted. To ensure transparency, all incentives granted should require Cabinet and Parliamentary approval and information on incentives granted made publicly available through gazette notices. Sunset clauses will ensure that incentives have a limited timeframe and are periodically reviewed.

Conducting tax expenditure analysis

Tax expenditure refers to concessions such as tax exemptions, deductions, concessionary tax rates, etc. granted to specific industries or entities. While typically a government budget provides estimates of government revenue, tax expenditures are rarely reported. However, given the generous tax incentives offered it is vital to ensure the costs and benefits of tax expenditures are properly accounted for. Conducting regular tax expenditure analysis will enable comprehensive cost benefit analysis to evaluate the potential revenue loss and the expected economic benefits of tax incentives. Moreover, it is essential to carry out regular assessments to ascertain whether the revenue loss resulting from tax exemptions is justified by the employment, GDP contribution, and economic impact of these projects.

Global Minimum Tax 5

When tax incentives and holidays are granted, it should be ensured that their rates are not lower than the rate recommended by the Global Minimum Tax (GMT). This is an agreement introduced by the OECD/G20 in October 2021, with the purpose of establishing a minimum tax rate of 15% for large multinational companies. It allows countries with taxable parent companies of Multinational Enterprises (MNE) to impose a top-up tax on the profits of any foreign subsidiary that pays an effective rate less than 15%. It also allows the host country where the MNE subsidiary carries out its activities to charge a top-up tax rate on subsidiaries, if the home country of the parent company imposes a CIT rate less than 15%. So even if the countries are free to grant tax holidays and incentives with a CIT rate lower than 15%, the agreement grants the taxing rights to either the FDI exporting countries or the countries in which the MNE subsidiaries are operated. Therefore the MNEs would not be benefitted by lower rates as they will be taxed by either country.

The countries that do not adopt this GMT rule would lose out on tax income as the other countries will adjust their domestic tax rules to top up undertaxed profits. This proposal has already been strongly backed by 130 countries. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka was one of the nine countries that did not agree to this proposal.

The country is struggling to meet its revenue targets. The potential of CIT as a significant source of revenue has not been not fully exploited. A plethora of tax incentives granted under numerous agencies have seriously eroded the tax base. Reversing these trends are vital for restoring fiscal sustainability and enabling the Government to promote sustainable and inclusive growth.

Footnotes:

1This is due to the imposition of a retrospective one-time surcharge tax of 25% on individuals, companies, and partnerships with a taxable income exceeding 2 billion for the 2020/2021 tax assessment year.

2Based on the taxes paid by around 230 listed companies on the Colombo Stock Exchange in 2019/2020.

3Information on projects granted under the SDP Act are publicly available through gazette notices which are mandatory. This is unlike projects granted incentives under the BOI Act which are not publicly available. An RTI filed to extract this information was also not responded to by the relevant authority.

4http://documents.gov.lk/files/egz/2023/8/2343-60_E.pdf

5World Bank, 2023, “Can the global minimum tax agreement reduce tax breaks in East Asia?” https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/can-global-minimum-tax-agreement-reduce-tax-breaks-east-asia#:~:text=In%20October%202021%2C%20the%20G20,to%20be%20implemented%20in%202024.

(Roshan Perera is a Senior Research Fellow at Advocata Institute. She can be contacted via roshananne@gmail.com. Thashikala Mendis is a Data Analyst at Advocata Institute. She can be contacted via thashikala@advocata.org. Janani Wanigaratne is a Research Consultant at Advocata Institute. She can be contacted via janani.advocata@gmail.com.

The opinions expressed are the writers’ own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.)