By Dhananath Fernando

Originally appeared on the Morning

SriLankan Airlines (SLA) is not a new name in the country’s long list of financial headaches. It is our National Carrier, a symbol of pride when it flies, and a source of embarrassment when it falls into losses and political meddling. Governments have changed, but the story has remained the same.

Today, the situation is worse than ever. The airline is practically impossible to rescue in its current form. The previous Government invited investors to take over or partner with the airline, but not a single credible party showed interest. The reason is simple: the balance sheet is deeply negative.

Last year, SriLankan Airlines made a profit of about Rs. 7.9 billion. This year, it has reported a loss of about Rs. 2.7 billion. Some argue that the airline should remain under State control. But even if the Government wanted to divest, the question is who would want to buy an airline buried in debt.

The truth is, the problem is more serious than it appears. The saddest part is that there is no restructuring plan at all. The Government seems to have accepted the airline’s own proposals and continues to operate without a clear direction.

According to the National Audit Office, continuous Government support is required just to keep the airline running. Last year alone, taxpayers injected Rs. 20 billion into it.

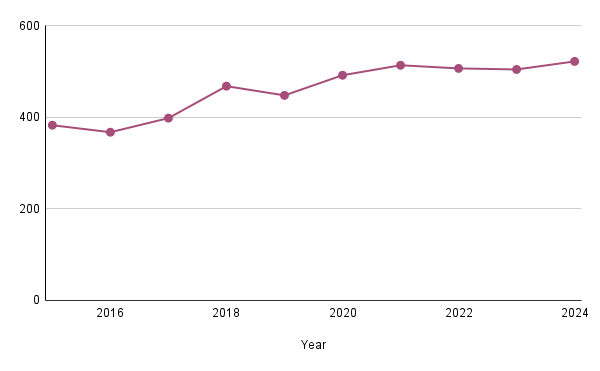

Let us look at how much public money has been spent over the years:

2010: Government buys back Emirates’ 43.6% stake for $ 53 million

2011/’12: Capital infusion of Rs. 14.3 billion through Treasury bonds

2014: Treasury settles Rs. 26.11 billion owed to the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) for unpaid fuel bills

2016: Cabinet approves absorbing Rs. 461 billion of SLA liabilities

2023–2024: Government agrees to absorb $ 510–553 million of SLA debt

H1 2024: Equity top-up of Rs. 5 billion for cash flow support

Budget 2025: Rs. 20 billion allocation for legacy debt service

Since parting ways with Emirates, we have repeatedly returned to the Treasury for help.

Even though the airline shows an operating profit, it is not enough. The load factor is around 70%, while the break-even point is about 76%. The main losses come from finance costs, which are roughly Rs. 30 billion each year — a huge amount compared to revenue.

To stay competitive, the airline needs investment to modernise its fleet and improve efficiency. But the Government has no funds, and no investor or lender will come forward without a Treasury guarantee. The new Public Debt Management Act makes such guarantees more difficult and costly.

Revenue and passenger numbers have also declined compared to the previous year, even as tourism recovers. According to the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority, SriLankan Airlines carries only about 27-30% of tourists, while nearly 70% arrive through other airlines. This suggests that service issues, repair delays, and stronger competition are taking away loyal passengers.

At the group level, monopoly businesses such as ground handling and catering help to cover some losses, but they also make the entire aviation industry less competitive.

Even if the airline were liquidated today, it would still need Rs. 379 billion to settle its debts. Around Rs. 90 billion is owed to State banks such as Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank. Writing off those loans would hurt the stability of the banking sector.

Despite its financial troubles, SriLankan Airlines still operates on important routes and has an excellent safety record. The brand has emotional value for many Sri Lankans, which is why restructuring will face resistance from employees, trade unions, and politicians.

So what can be done?

Option 1: Dress up the balance sheet once and for all. Inject the required taxpayer money, absorb the liabilities, and then look for a strategic investor.

We have tried partial fixes for years, taking over some debt and hoping the airline will perform better, but that approach has failed. If we want to attract a serious investor, we must clean it up completely and find a partner with deep experience in aviation.

However, this must be done with a clear legislative direction and timeline. Otherwise, once the debt is absorbed and the airline begins to show a profit, a new debate will arise questioning the need to privatise a profit-making National Carrier. The political economy will then move quickly to block reform, forgetting that the taxpayer had already paid for the cleanup.

Option 2: Package SriLankan Airlines with other State assets such as the Mattala or Ratmalana airports to make it more attractive to investors.

This might require relocating some Air Force operations and preparing a comprehensive restructuring plan. But such an approach takes time, and time is exactly what we do not have. The longer we wait, the deeper we fall, and the more political and geopolitical interests get involved.

There is no point blaming the airline or its employees. The problem is not in the sky but on the ground. We simply have no plan.

It is time to get our act together, because a national airline without a flight plan can only keep flying in circles.