By Dhananath Fernando

Originally appeared on The Morning

Last week, former Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India Arvind Subramanian delivered a talk organised by a local media outlet and repeated a message this column has been making for years. Sri Lanka has become a permanent client of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). His uncomfortable question was simple: have we really addressed the reasons we keep returning to the IMF?

The IMF is not the problem. The real problem is what we repeatedly do, and fail to do, that pushes us back to the IMF. We postpone reforms. We dilute reforms. We announce reforms and then negotiate with ourselves until nothing meaningful remains. That is how a country ends up treating the IMF like a recurring subscription, not a last-resort lender.

We are now back again, for what feels like the umpteenth time, still asking for breathing space while keeping the deeper structural issues on hold. The tragedy is not the programme. The tragedy is the pattern.

One of Subramanian’s most important warnings was about memory. Sri Lankans must not forget the economic crisis. Most reforms we managed to pass were done at the height of pain, when denial was no longer possible. Once the pain fades, our political system starts behaving as if the crisis was a bad dream, not a diagnosis. History shows that when we forget the lesson, we repeat the bill.

To be fair, this time we do have a few structural reforms in place. The Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s greater independence, the Public Debt Management Office and framework, the fuel price formula, the Public Financial Management Act, and the Anti-Corruption Act are steps that bring more discipline to the system. They help reduce policy chaos. They improve predictability. They can strengthen credibility.

But we must be clear about what they are, and what they are not. Stability is not reform. Stability is not the same as growth. Stability is the floor, not the ceiling. It prevents the economy from collapsing again. It does not automatically make the economy expand.

Subramanian also stressed something that Sri Lanka often tries to ignore: stability has to be continuously defended through reforms. Without economic stability, growth is simply impossible. As the saying goes, stability is not everything, but without stability everything is nothing.

Yet even if we get stability right, we cannot ignore the fundamental shift happening in our demography, which will shape every economic outcome over the next decade. Our labour force is ageing and our population is shrinking. That means a smaller base of working people will have to carry a larger burden: elderly citizens who need care and income security, and younger citizens who still need education and investment. If productivity does not rise, the arithmetic will not work.

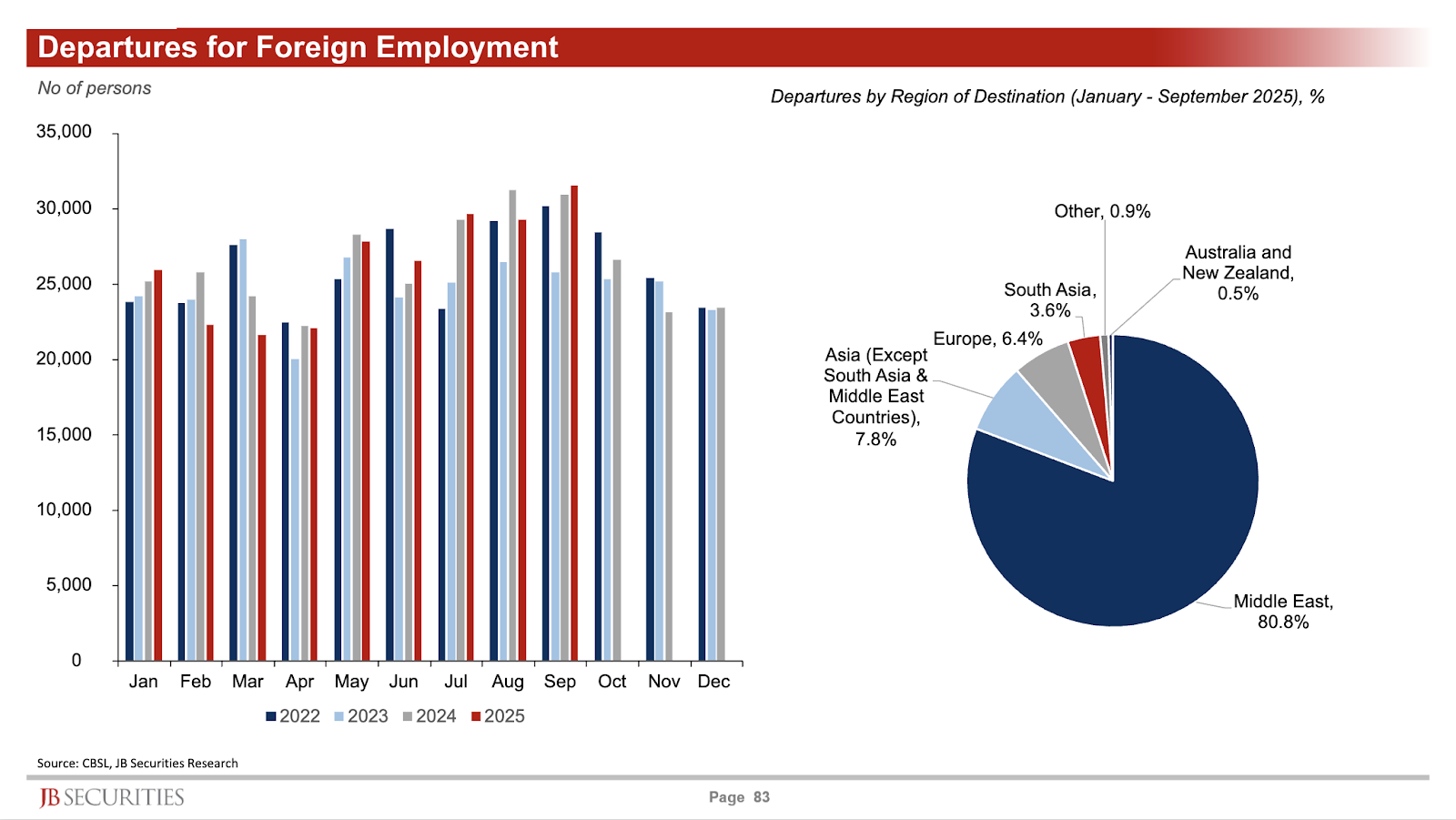

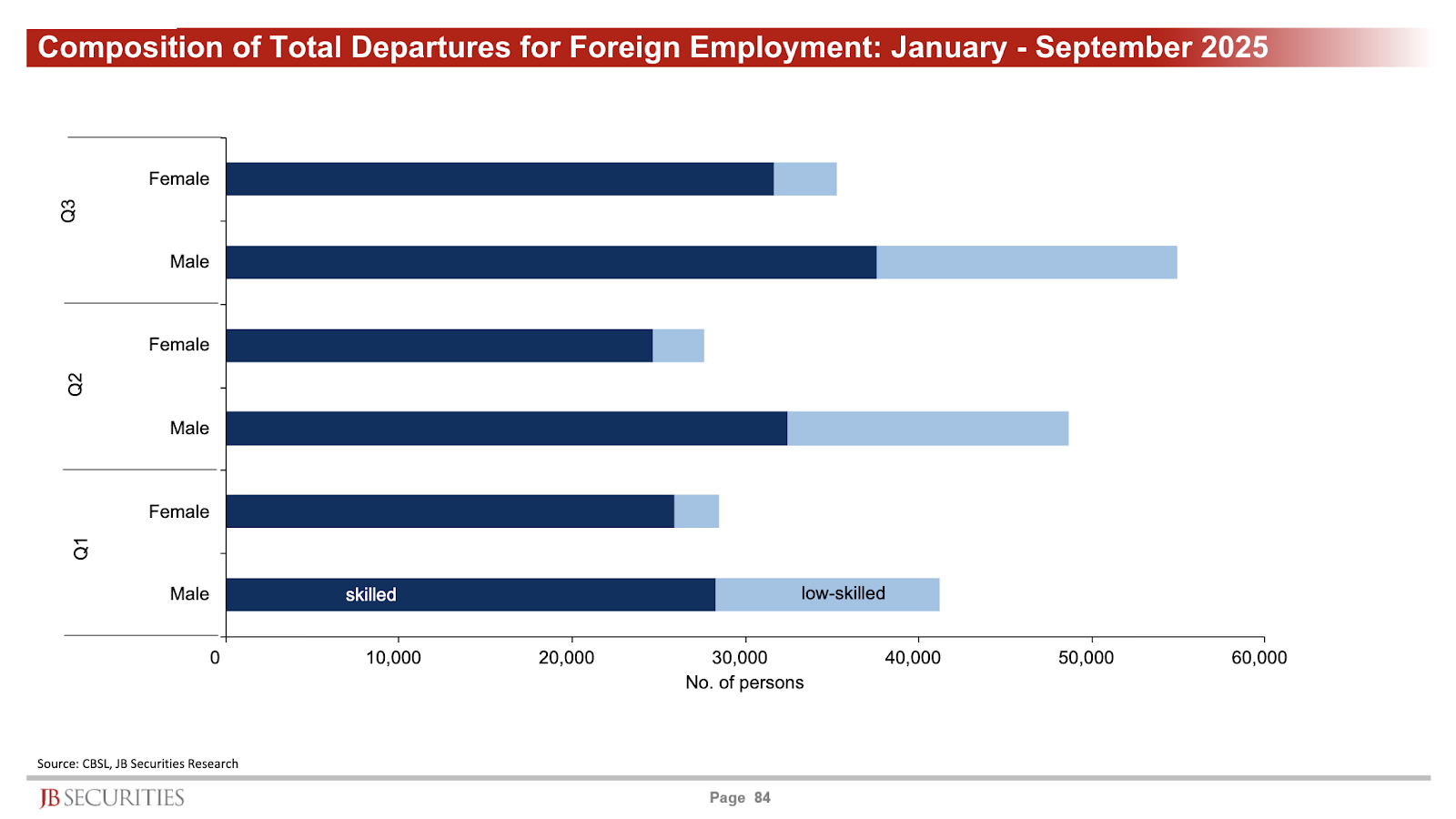

The outlook becomes even more worrying when we look at how our labour migration patterns are changing. We proudly celebrate rising remittances, and the headline numbers look comforting. But the composition behind those numbers tells a more serious story. The old perception that Sri Lanka’s out-migration is mainly unskilled women leaving for domestic work is no longer accurate. Increasingly, our out-migration is skilled and male.

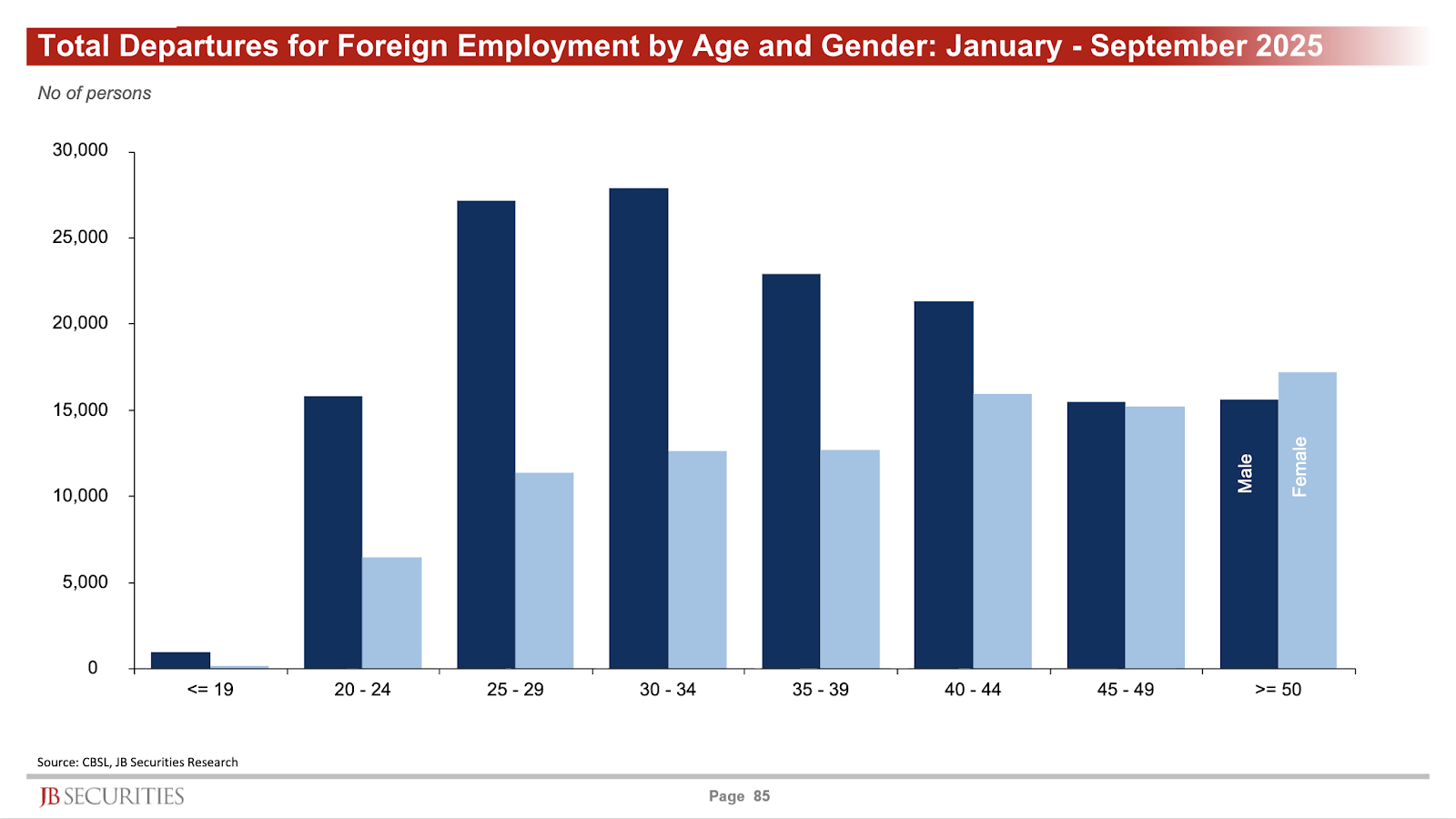

Recent quarterly trends show that it is largely skilled males in the prime working-age bracket who are leaving. And when we look at destinations, with a few exceptions, the pattern again points to a labour export profile dominated by skilled men. In simple terms, the country is losing the very workforce it needs for growth, productivity, and tax revenue.

At the same time, we are failing to solve the long-standing problem of low female labour force participation. We have discussed this for years. We have had commissions, reports, policy notes, and conferences. The conclusions are broadly consistent. But the reforms remain stuck.

Contributory pension schemes that create portability and security, flexible work arrangements that fit modern households, clear part-time work regulations, and enabling rules for gig and platform work are not ‘nice to haves.’ They are core reforms for an ageing society with a shrinking workforce. Delaying them is not neutral. The costs will show up through slow growth, weaker productivity, and a narrower tax base.

These are the kinds of reforms Subramanian may not have listed one by one, but his point was clear: we have not done a good job of getting the right things done to ensure we do not return to the IMF again.

Both economic stability and economic growth are difficult games to play. The danger is thinking we can remain stable without growing. Stability cannot be sustained without growth. But growth also cannot be achieved without reforms, and reforms create political pressure, which can tempt governments to return to short-term populism and policy reversals. That push and pull is the real challenge.

This is a delicate balance, and failing to manage it will cost us dearly: by eroding hard-earned wealth, weakening institutions, and drifting back into crisis. Or, as Subramanian bluntly framed it, drifting back to the IMF.

The IMF is not the problem. What we keep doing to end up back there is the problem.

Departures for foreign employment

Source: CBSL, JB Securities Research

Composition of total departures for foreign employment: Jan.–Sept. 2025

Source: CBSL, JB Securities Research

Total departures for foreign employment by age and gender: Jan.–Sept. 2025

Source: CBSL, JB Securities Research