Originally appeared on The Morning.

By Dr. Roshan Perera

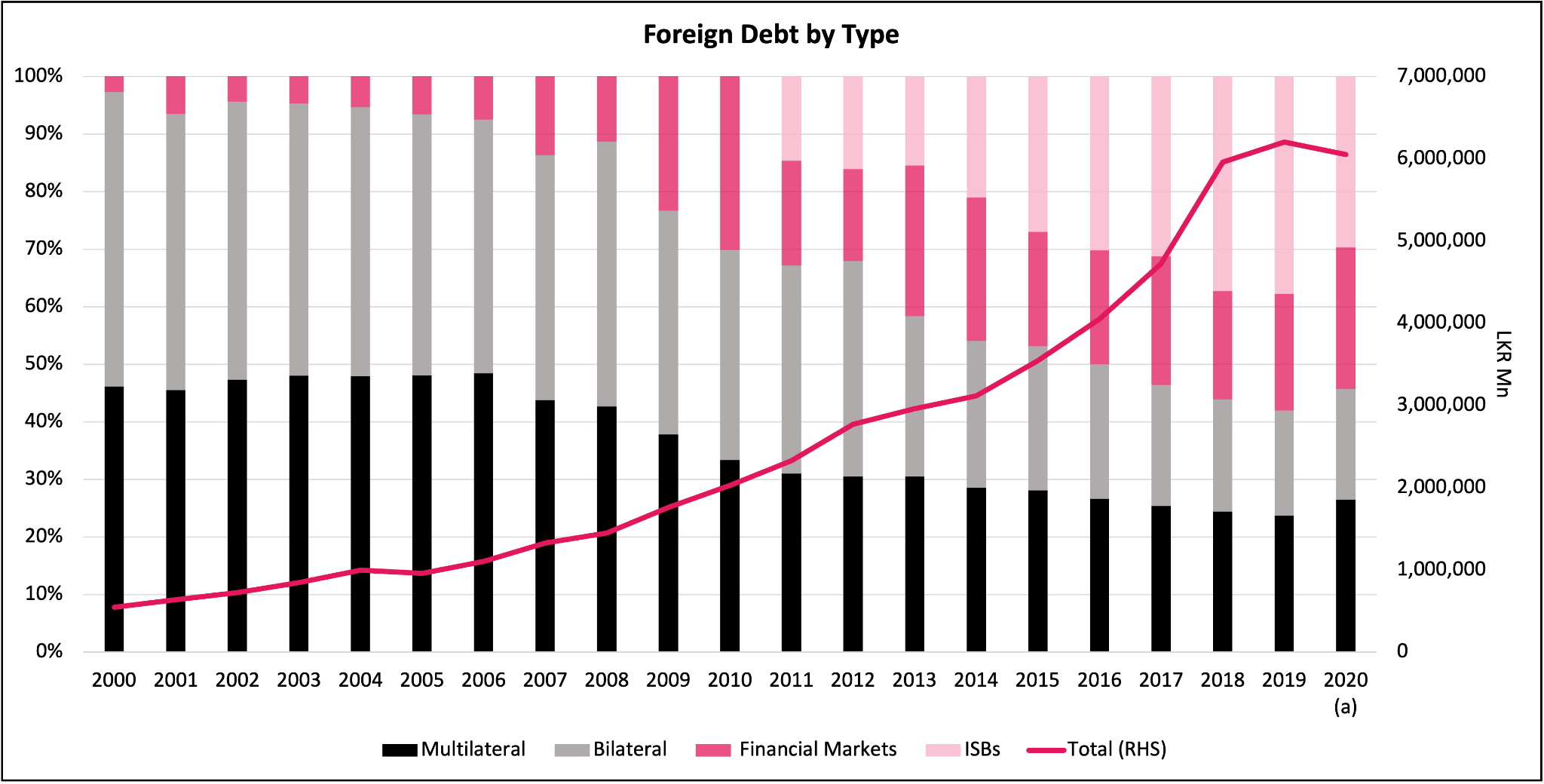

Years of profligate living finally caught up with us. Sri Lanka, for much of its post-Independence period, has been living beyond its means: We have been spending more than we earn and consuming more than we produce. Our extravagant lifestyle was made possible by the availability of concessional financing from multilateral and bilateral donors. This ended once we graduated to a middle-income country. But we didn’t change our spending patterns to match our income. Instead, we sought alternative sources of financing. We borrowed from financial markets and commercial sources at high interest rates and with shorter repayment periods.

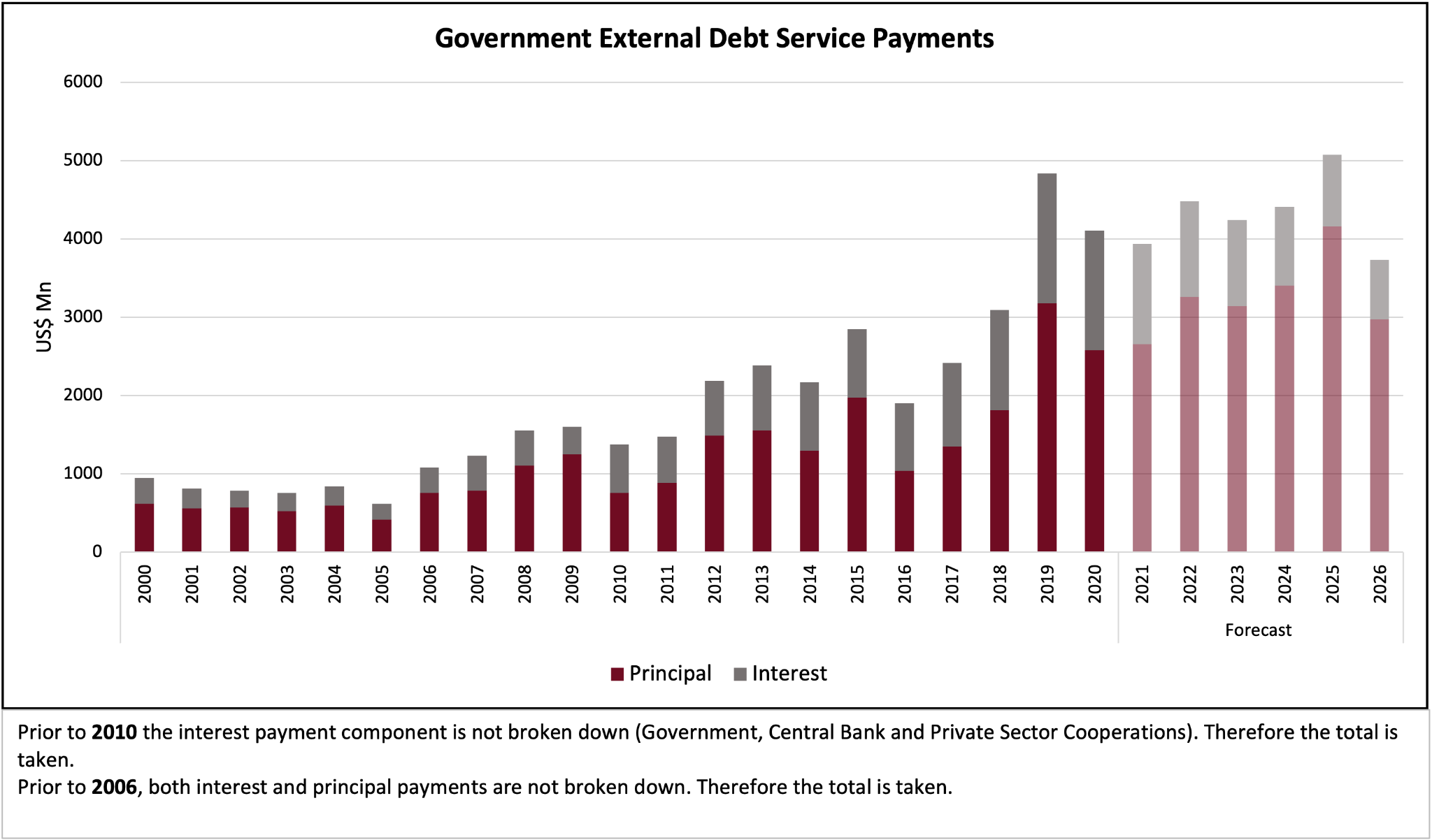

Consequently, by 2016, the share of foreign debt from non-concessional sources rose to over 50%. This had an enormous impact on our debt service payments. Today, Sri Lanka has one of the highest levels of government debt in its history and its debt service payments are one of the highest in the world (absorbing 72% of government revenue in 2020). This led to both domestic and external resources being diverted to servicing past debt to the detriment of future growth.

According to current estimates, Sri Lanka has around $ 26 billion in foreign debt obligations due between now and 2026. Sovereign rating downgrades made rolling over this debt challenging. But these are contractual obligations and there could be serious repercussions if a country defaults on its debt. Due to the decline in foreign inflows owing to the pandemic, the Government resorted to short-term measures such as bilateral swaps to shore up foreign reserves. However, there was a steady drawdown of the country’s foreign reserves to meet these debt obligations. Foreign reserves, as at end-September 2021, declined to $ 2.5 billion (which was equivalent to 1.5 months of import cover). Foreign currency obligations falling due within the next 12 months amount to around $ 7 billion. The current level of foreign reserves is grossly inadequate to service the Government’s debt.

Furthermore, using a country’s foreign reserves to pay debt obligations is not a good strategy in the long term. Foreign reserves play an important role in an economy – by providing a buffer against possible external shocks, smoothing temporary fluctuations in the exchange rate, and providing confidence to foreign investors.

With limited access to foreign financing, the Government is relying more on domestic sources to bridge the fiscal deficit. To keep interest costs low, domestic interest rates have been suppressed, which has effectively dried up the market for government securities. This has led to debt monetisation, with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) purchasing a major share of government securities issued in the primary auction. However, there are costs involved with this strategy, as high monetary growth leads to high inflation. It also undermines the independence of the CBSL and hinders its use of its key monetary policy instrument, the interest rate, to manage inflation.

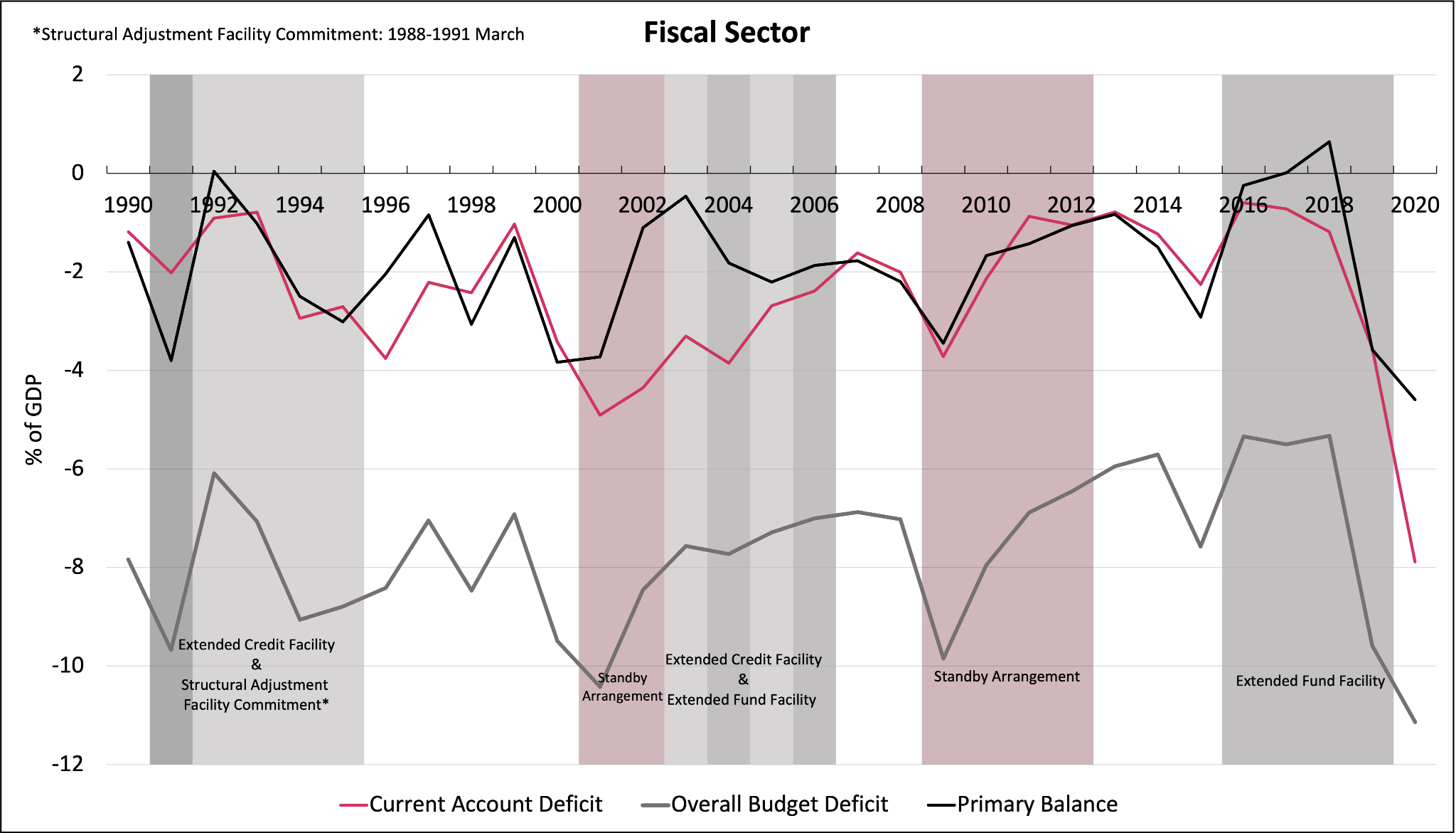

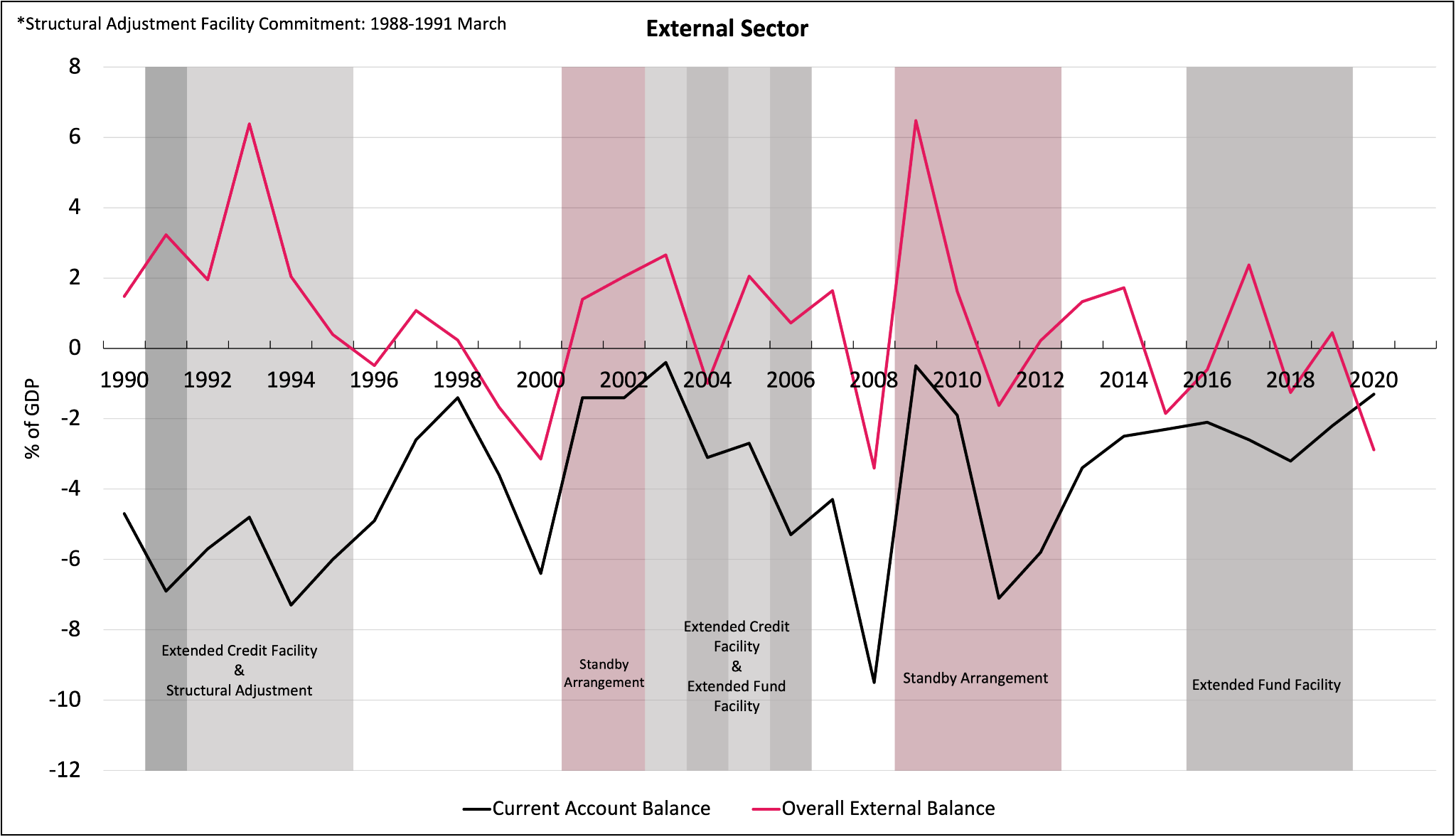

So, what needs to be done? Advocata Institutes’ recent report titled “A Framework for Economic Recovery” proposes several policies to address macroeconomic imbalances and structural reforms for sustainable and inclusive growth. These policies are not new. If you examine macro stabilisation programmes that have been implemented in this country (or in other countries that have faced similar economic issues), you would broadly find similar recommendations. This does not mean the recommendations made in the past were wrong – but rather that successive governments did not follow through on the reforms needed to ensure long-term macroeconomic stability and sustained economic growth.

This time is different in one aspect. Sri Lanka has lost access to financial markets due to its rating downgrade. Hence, it is not able to easily refinance its foreign debt. In previous stabilisation programmes, although debt sustainability was a major concern, it was addressed through a fiscal consolidation programme. This alone may not be sufficient in the current context. The country may need to engage in a pre-emptive debt restructuring exercise to prevent default. A wilful default could disrupt access to future financing, reduce investor confidence, affect credit ratings, and have a negative impact on the reputation of the country. However, debt restructuring is a complex process and securing a deal that is acceptable to a majority of creditors is fraught with difficulty, as there are many stakeholders involved, and conflicts of interest are inevitable, hence the need to engage with an institution such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the negotiation process.

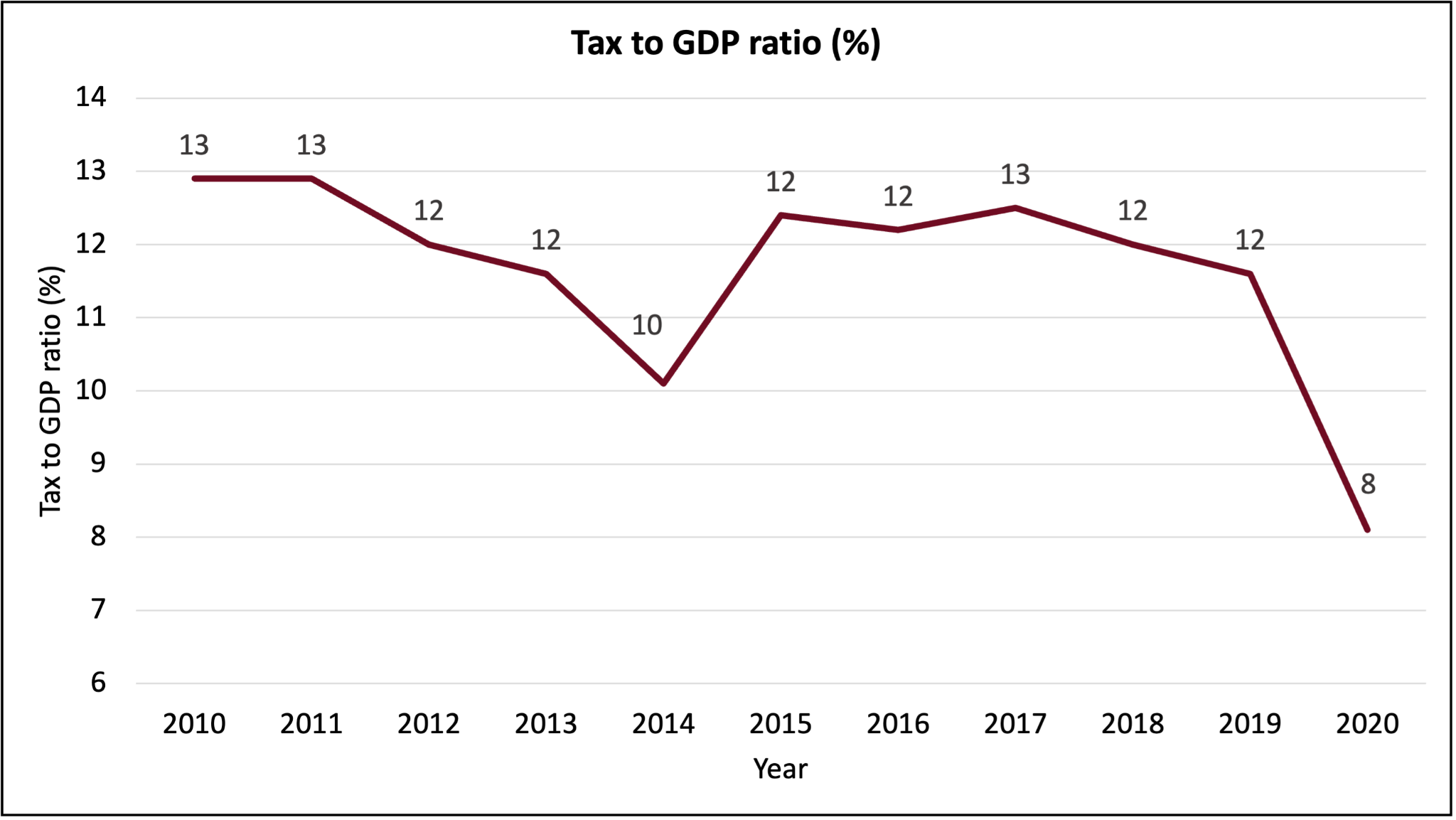

The focus of Budget 2022 should be to address the macroeconomic imbalances in the economy. Primarily, correcting the twin deficits, i.e. the fiscal deficit and the external current account deficit, because these have spillover effects into the rest of the economy through interest rates and exchange rates. Priority should be given to fixing the tax system. Tax revenue, which was over 20% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the 1990s, has plummeted to 8% in 2020 and is likely to fall further in 2021. Expanding the tax base and improving tax administration are key to reversing the long-term downward trend in government revenue.

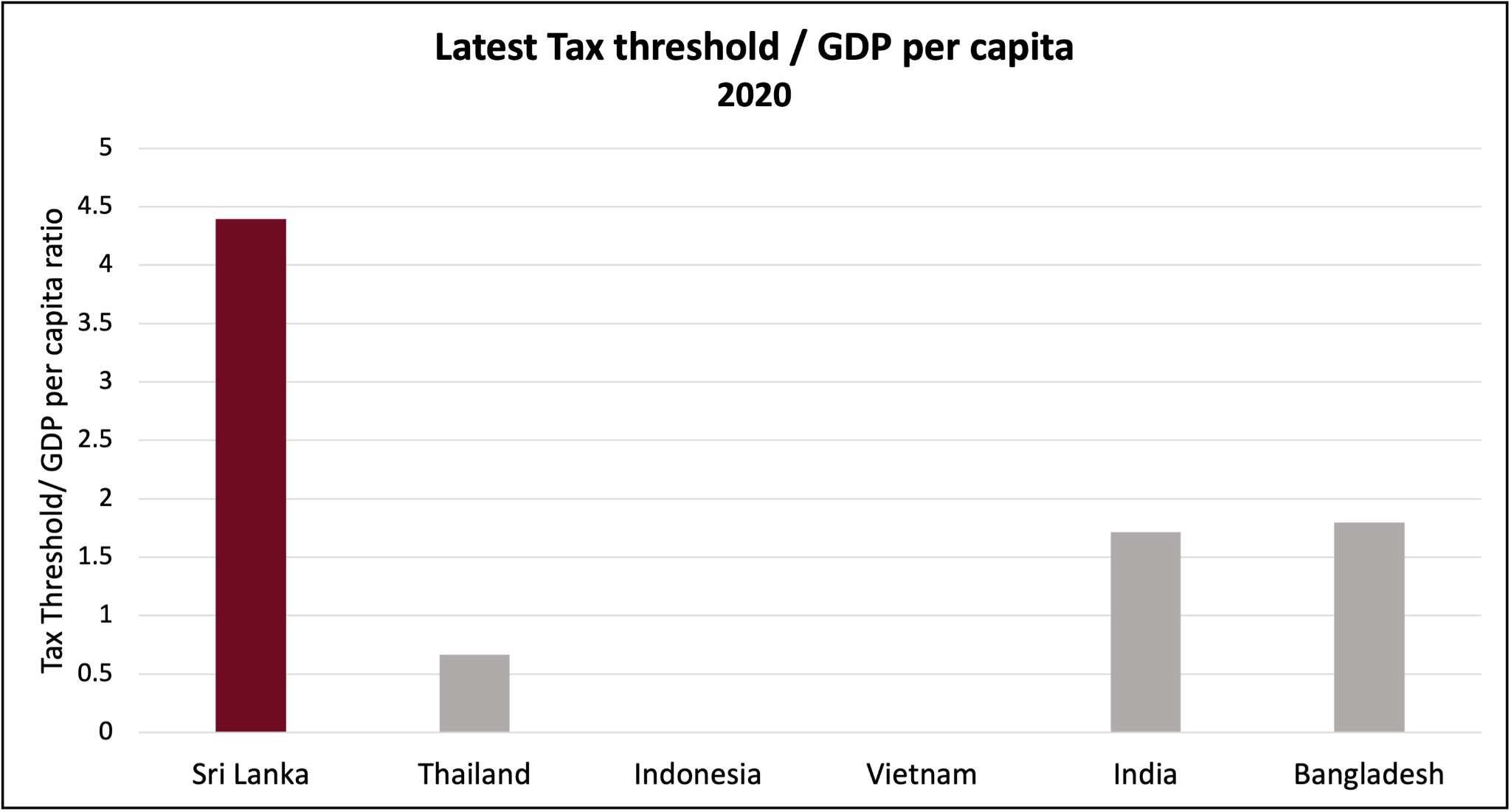

Currently, the income tax threshold in Sri Lanka is more than four times its per capita GDP and even higher than the tax threshold in countries with per capita incomes that are several times that of Sri Lanka, such as Singapore and Australia. A high tax threshold removes a significant portion of the working population that can contribute to tax revenue. Tax exemptions should be rationalised and the granting of exemptions centralised under one authority. Evidence suggests that sweeping tax exemptions is not the most important factor in attracting investments, and foregoing this tax revenue is not sustainable in the long term. With declining tax revenue collection, the Government faces severe resource constraints. Expenditure on contractual obligations (interest payments, salaries and wages, and pension payments) has come at the cost of spending on building human capital (health and education). This needs to be reversed. Serious attention needs to be paid in the budget to rationalising the public sector and strengthening budgetary oversight mechanisms so that the Government is held accountable for how they use the resources entrusted to them.

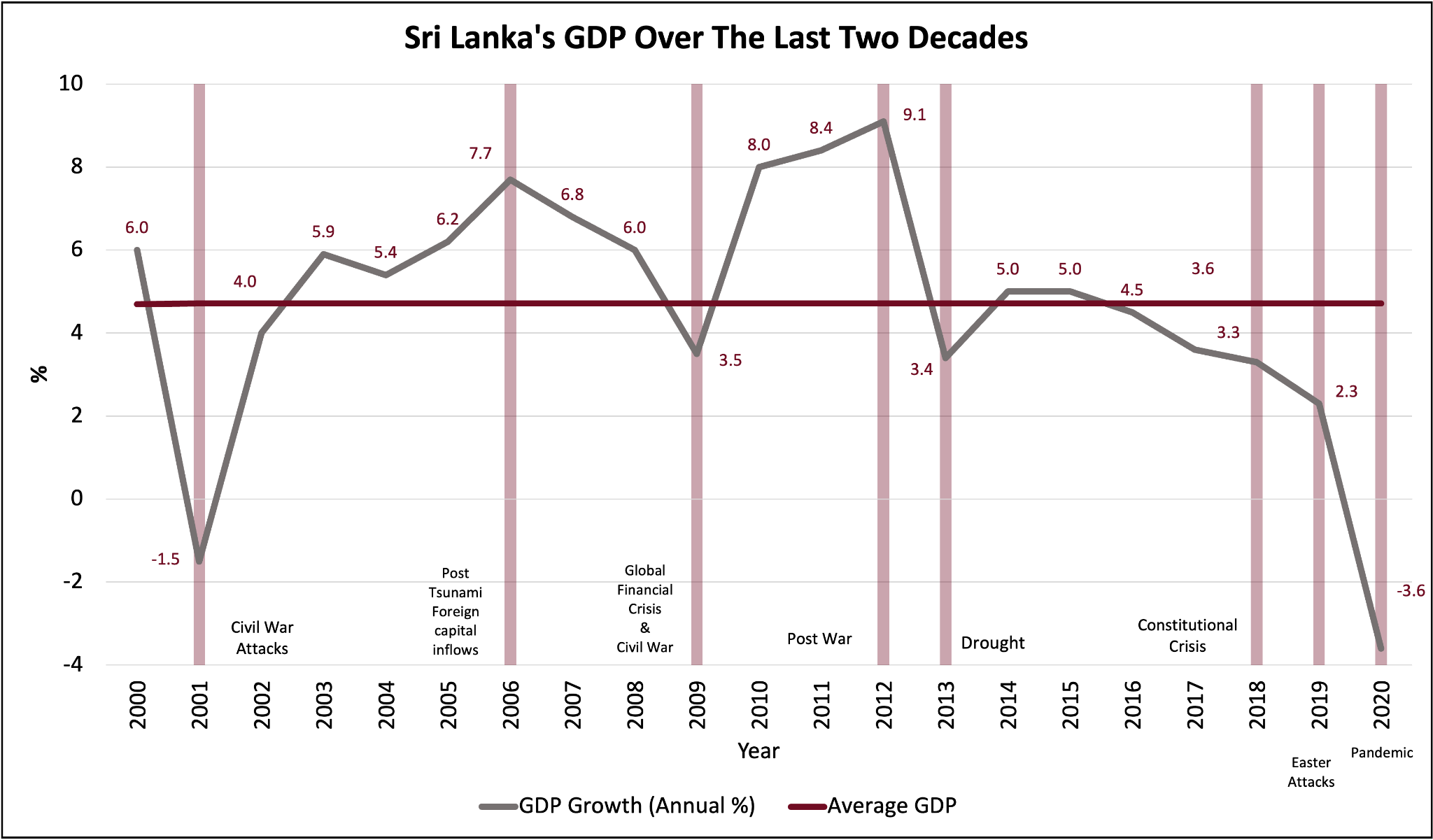

Secondly, we need to stimulate economic growth and improve the country’s competitiveness. Sri Lanka has experienced very volatile growth rates and in recent times, sudden spurts of debt-fuelled economic growth. But this growth has neither been inclusive nor sustainable. We need to generate growth that is both inclusive (benefits all our citizens) and sustainable (growth that does not jeopardise future generations). The budget needs to address the structural weaknesses in the economy hindering productivity-driven growth. Some policies that we discuss in our report are:

Improving the business environment by reducing regulatory barriers, which is needed to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). Sri Lanka lags behind its peers in the areas of doing business and competitiveness

Unlocking access to land that has been identified as a major bottleneck for investment

Creating a flexible labour market and raising labour force participation. There are a plethora of legislation governing labour in Sri Lanka which act as a serious impediment for job creation. Furthermore, Sri Lanka has a rapidly ageing population and is no longer benefitting from a demographic dividend. However, it has access to a large untapped source of female labour. Encouraging greater female participation in the labour force requires removal of legislation restricting employment of female workers and improved infrastructure such as childcare and safe transport services

Addressing infrastructure gaps to enhance productivity and efficiency of the factors of production. We need to invest in infrastructure that has high social and economic returns. This requires better processes for project appraisal and selection, better management of risks which otherwise could lead to cost overruns and project delays, and greater accountability to reduce waste and corruption.

Finally, the budget needs to build buffers to strengthen the resilience of the economy to shocks. Households have been disproportionately affected by the ongoing pandemic because they lack the buffers to cushion them from economic shocks. Workers, particularly in the informal sector, have lost jobs due to the impact of lockdowns and the closure of borders. Although the Government provided some relief to households affected by the pandemic by way of income transfers, the lack of fiscal space constrained the Government’s ability to adequately respond to the crisis.

In addition, Sri Lanka’s existing social protection scheme has significant coverage gaps and needs to be extended to include informal sector employees, daily wage earners, and self-employed workers. Ad hoc payments are not sufficient to keep people from falling into poverty. Urgent action is needed to establish a universal social safety net and reduce targeting errors to ensure those who need support receive it when they need it most.

Micro, small, and medium-scale enterprises (MSMEs) play a vital role in the Sri Lankan economy, accounting for over half of Sri Lanka’s GDP and over 90% of total enterprises and 45% of employment in the non-agriculture sector. This sector was severely affected by measures taken to contain the spread of the virus, such as travel bans, lockdowns, and social distancing. To mitigate the impact of the pandemic, the Government and CBSL introduced various emergency liquidity support programmes, debt moratoriums, and extension of facilities at concessionary interest rates. While these schemes may have prevented some firms from bankruptcy, the Government is unable to continue providing such relief, given the prolonged nature of the pandemic and the fiscal constraints it faces.

However, given the size of this sector and its importance to the economy, ensuring the solvency of these firms as well as increasing their productivity is paramount to Sri Lanka’s long-term economic growth prospects. As the pandemic continues to affect economic activity, many firms will emerge with serious impact on their balance sheets. Therefore, as economies transition to normalcy, it is important to repair balance sheets by reducing unsustainable debt and rebuilding cash reserves. Firms that are not resilient, are uncompetitive, or are heavily indebted will collapse during such crises. To reduce the adverse economic impact of ad hoc closures in the most productive manner, the Government must ensure access to an effective bankruptcy regime. Such a mechanism will strengthen economic resilience, while incentivising firms to prioritise strategies to repair balance sheets in the medium term before they reach bankruptcy.

In conclusion, the key focus of policymakers should be on addressing macroeconomic imbalances. Priority should be given to correcting the twin deficits, i.e. the fiscal deficit and the external current account deficit, stimulating economic growth, and improving competitiveness while building buffers to strengthen the resilience of the economy to shocks.

(The writer is a Senior Research Fellow at the Advocata Institute and a former Director of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka)