By Dhananath Fernando

Sri Lanka’s construction cost problem

The Government has announced Rs. 5 million for houses completely destroyed by Cyclone Ditwah and up to Rs. 2.5 million for houses that are partly damaged. Bridges and a lot of civil infrastructure have been damaged.

On the other side, the Government has announced a Rs. 200,000 initial relief package for Micro, Small, and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs). The Central Bank of Sri Lanka has also requested Licensed Commercial Banks (LCBs) to offer a loan moratorium of 3–6 months for affected businesses.

These measures are meant to help people rebuild their lives and restart the economy. But there is one vital reform missing from the response. If we ignore it, even well-intended relief will deliver less than promised.

That reform is lowering the cost of construction.

This crisis has created a rebuilding requirement at a scale that no one can ignore. As per released data, about 5,000 houses have been completely destroyed and about 87,000 houses are partly damaged. More than 40 bridges have been affected, and flood waters have reached more than 720,000 buildings, including schools and hospitals.

The damage goes far beyond housing and bridges. A further 1,777 tanks, 483 dams, 1,936 canals, and 328 agricultural roads under the Department of Agriculture have been damaged.

You do not need to be an economist or a financial analyst to understand what this means. Rebuilding will require an enormous volume of construction work. Even the smallest repair job requires materials. A partially damaged house may need new switches, repainting, replacement tiles, and electrical wiring checks after floods. Public buildings will need similar work, while roads, canals, tanks, and dams will need steel, concrete, and heavy repair inputs.

This is precisely why Sri Lanka’s cost of construction becomes the real litmus test of our crisis response.

Sri Lanka’s cost of construction is higher than the region. Worse, the tariff rates on basic construction materials are so high that one can only describe them as inhumane. Housing is a basic need, especially in a disaster. Yet we continue to push up prices through taxes and para-tariffs that make rebuilding unnecessarily expensive for families and for the State.

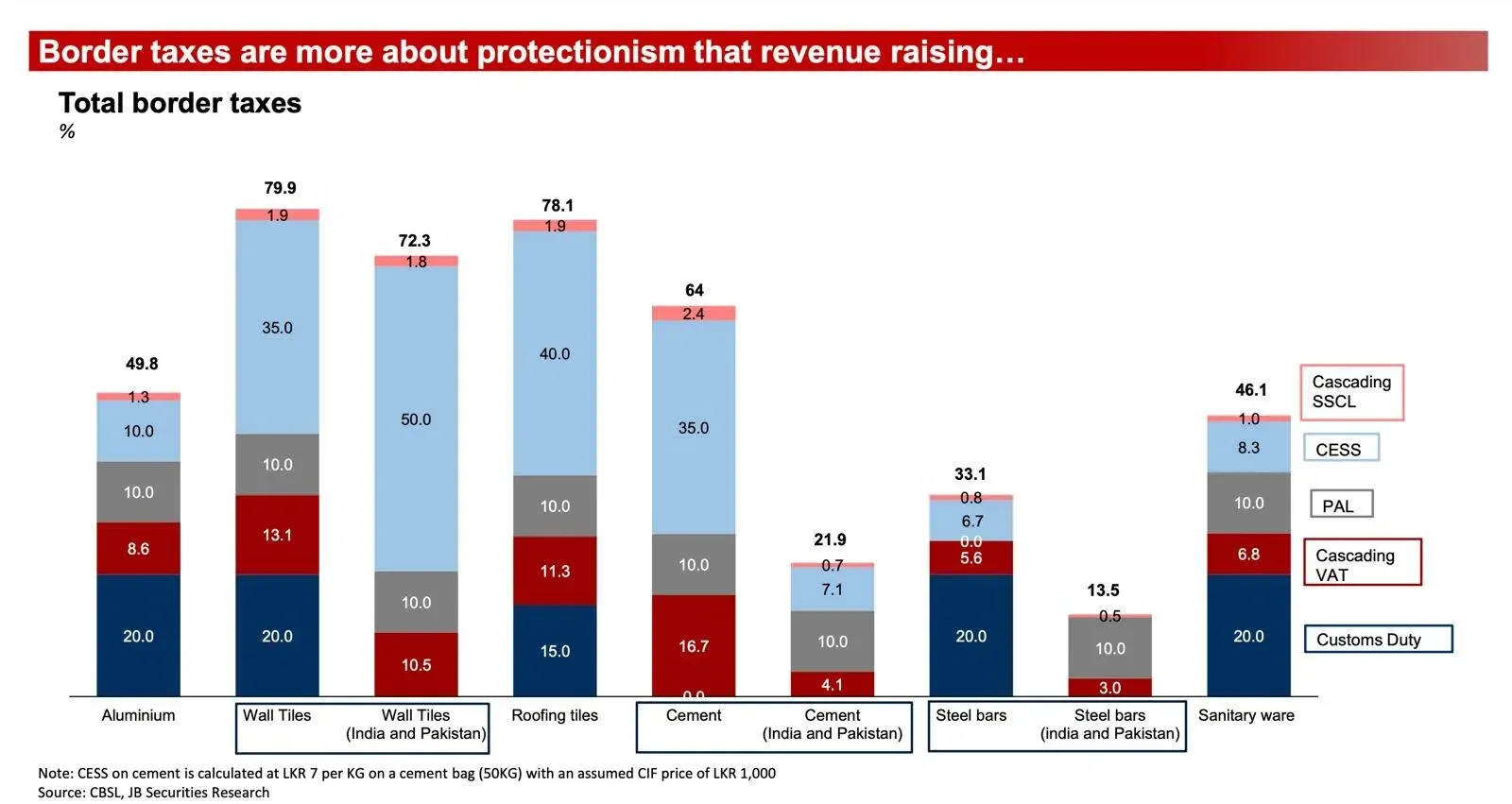

Consider just a few examples. The total tariffs on steel bars is 33%. The total tariff for cement is 64%. Tariffs on wall tiles are 80%. Sanitaryware is 46%. Aluminium is about 50%. When these numbers sit on top of a massive rebuilding effort, it becomes obvious that a large share of what the Government allocates for construction-related rebuilding ends up as taxes and para-tariffs embedded in prices.

Some may argue that these tariffs help raise revenue to redistribute to cyclone-affected people. But the reality is different. Many of these tariffs are not designed primarily as revenue measures. They are designed to block competition.

Just think about it: why would anyone import when there is an 80% tariff rate? Yet in some sectors, imports still happen even at such rates, because even after paying the tariff, the imported product is cheaper than some local items protected behind these same barriers.

That should tell us something uncomfortable. If the Government does not reduce construction-related tariffs, a significant portion of ‘relief’ becomes indirect support for unproductive, protected businesses. In other words, the country attempts to rebuild after a disaster while keeping policies that quietly inflate the bill and reward rent-seeking.

During the crisis, there was a powerful story that Welikada Prison inmates contributed one meal for those affected. Even prisoners were willing to compromise. Now imagine, at the same time, the State maintaining a policy environment that creates room for excessive profits for protected sectors in one of the worst crises Sri Lanka has faced. That is not just bad economics. It is morally indefensible. It will not pass the test of any moral compass.

There is also an international dimension that the Government cannot keep dodging. The World Trade Organization (WTO) does not permit customs duty in excess of 30%. Sri Lanka imposes the Ports and Airports Development Levy, the Commodity Export Subsidy Scheme (CESS), Value-Added Tax (VAT), and Social Security Contribution Levy (SSCL), all of which have a cascading impact.

These layers are used to find loopholes in WTO guidelines, but the economic outcome is simple: higher prices, lower competitiveness, and a heavier burden on citizens at the worst possible time.

So the question of whether the Government is willing to change tariffs on construction is not just a test of the influence of certain rent seekers. It is a test of common sense and a test of our humanity. If we are serious about rebuilding after the cyclone, the Government must remove these additional tariffs and bring the cost of construction down for all those affected.

If we fail, we will not only fail families trying to rebuild homes. We will fail as a nation trying to recover with dignity.