Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

I had a friend in school whose aspiration was to be the president of Sri Lanka. One day, our school teacher asked him: “So what are you going to do when you become the President?”

He had a simple answer. “I am going to end poverty in Sri Lanka and make all citizens wealthy by ensuring they all have enough money.” In response, the teacher further questioned: “How are you going to do it?” To which my friend answered: “It’s not difficult. I will print money and distribute one million per citizen among all citizens so they have money to buy all the goods and services they want.”

This sounded like a great idea to schoolboys who did not know anything about economics. “Why can’t governments print money and increase the income of people and allow them to buy goods and services as they wish?” were our initial thoughts.

The teacher then questioned: “What if the market doesn’t have enough goods and services to buy with the money you expect to give away. Do you think that having money in hand but no goods and services in the market will help people consume what they need?”

Through my teacher’s counter-questioning I realised that “money” or fiat currency is just a piece of paper. The amount of goods and services we can buy from that money is what matters instead of the quantitative or numerical amount of money in hand.

Take a Rs. 100 note and a $ 100 note for example. Both of them might represent a 100 but we can buy more goods and services from $ 100 than Rs. 100. Therefore, managing “money” or the currency must be done very carefully.

The economy is a broader concept where the supply of money is just one tool within this system. This economic system performs the function of optimising limited and scarce resources to meet unlimited wants. Prices determine what could be bought or sold by the quantity of money.

If there is strong demand for one good over another, its price will go up and the supply of that good will go up, as producers try to make more money to get more profits.

Excessive creation of money without regard to the number of goods and services produced in a country leads to price inflation, which distorts relative prices. Sri Lanka’s economic problems are multifaceted. Therefore, we have to evaluate whether we can overcome our economic challenges by printing money as suggested by my school friend. This dilemma brings Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) into context.

Some advocates of MMT say money can be printed by governments without a problem. Other advocates say governments can borrow large amounts of money without a problem. At the end of the day, printing money is also a form of borrowing from the Central Bank. Still, other proponents say taxation can be used to stop the inflationary effect.

While different proponents of MMT have proposed slightly different views, some of the key ideas are that governments can increase deficit spending without a problem and that they can also print money. Still, others argue that money can be printed to repay bonds, and therefore there will be no default on debt.

However, it is important to remember that the comparison of a government to a household only goes so far. This is because sovereign nations can print money which a household cannot. Some believers of MMT claim that in an environment where a country hasn’t reached full employment, printing money or quantitative easing doesn’t cause inflation. Some others argue that if inflation picks up, taxation can be used to take spending power and reduce inflation.

When a country like Sri Lanka prints more money it can cause two problems. One is that it will

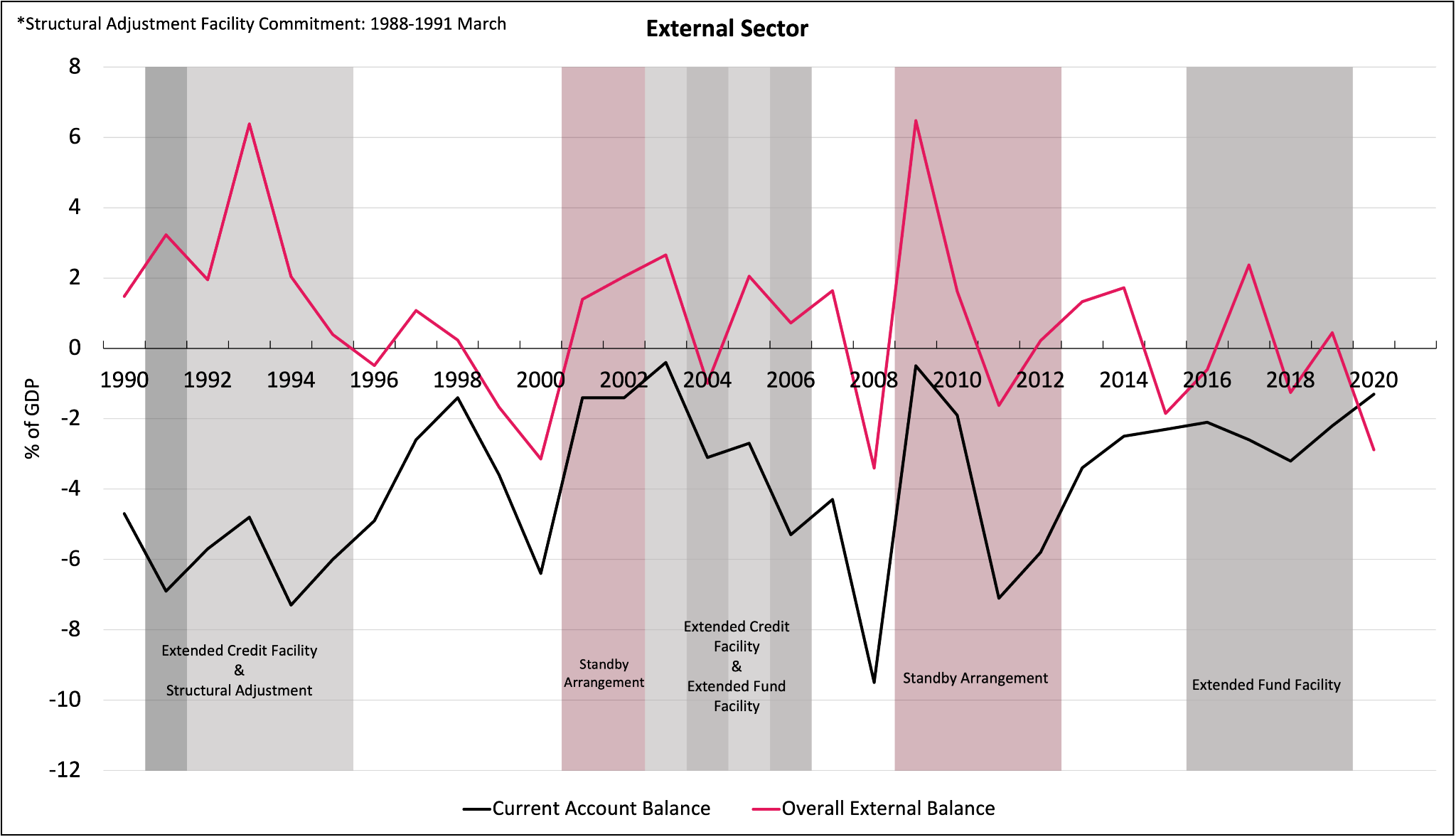

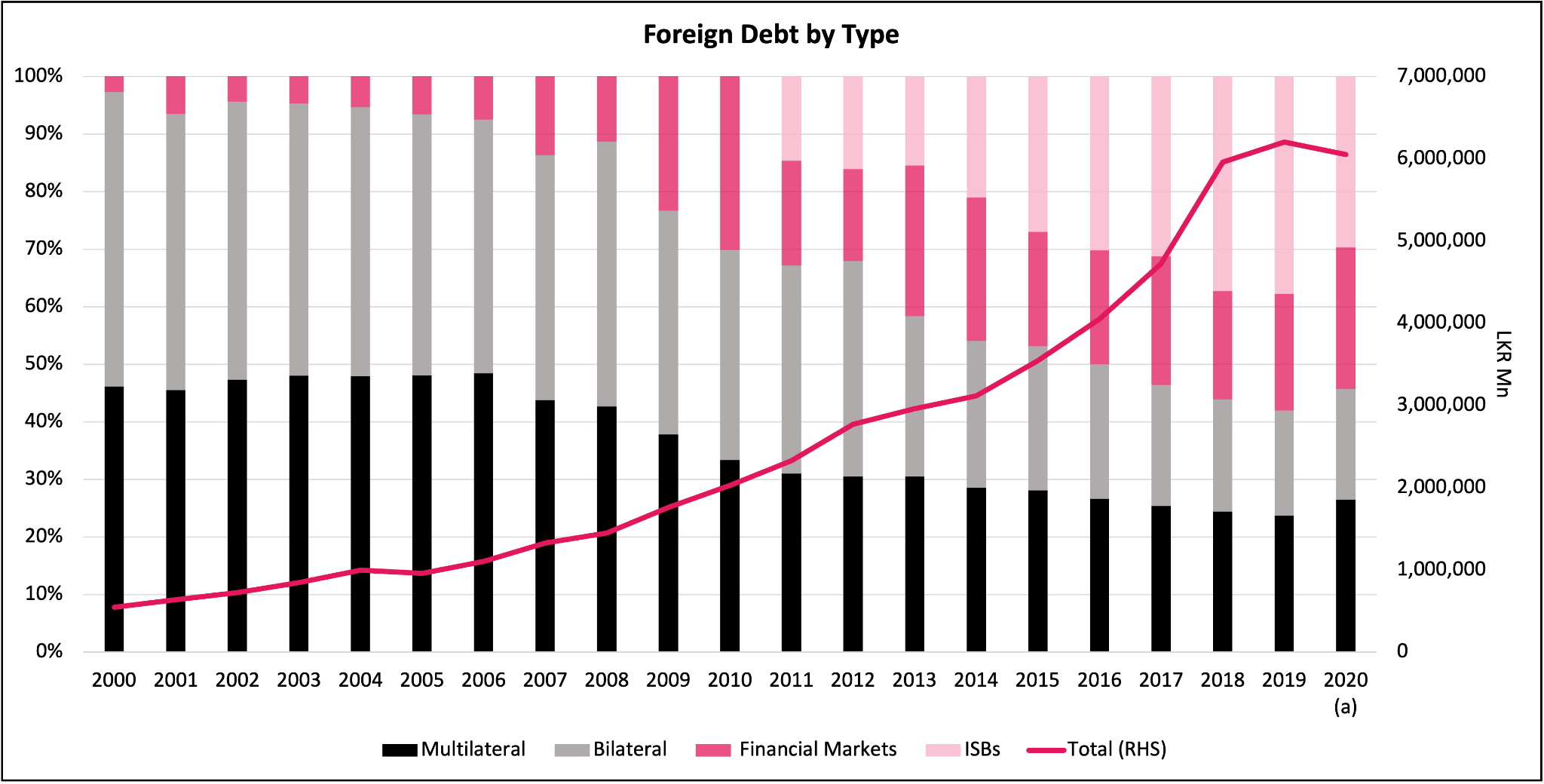

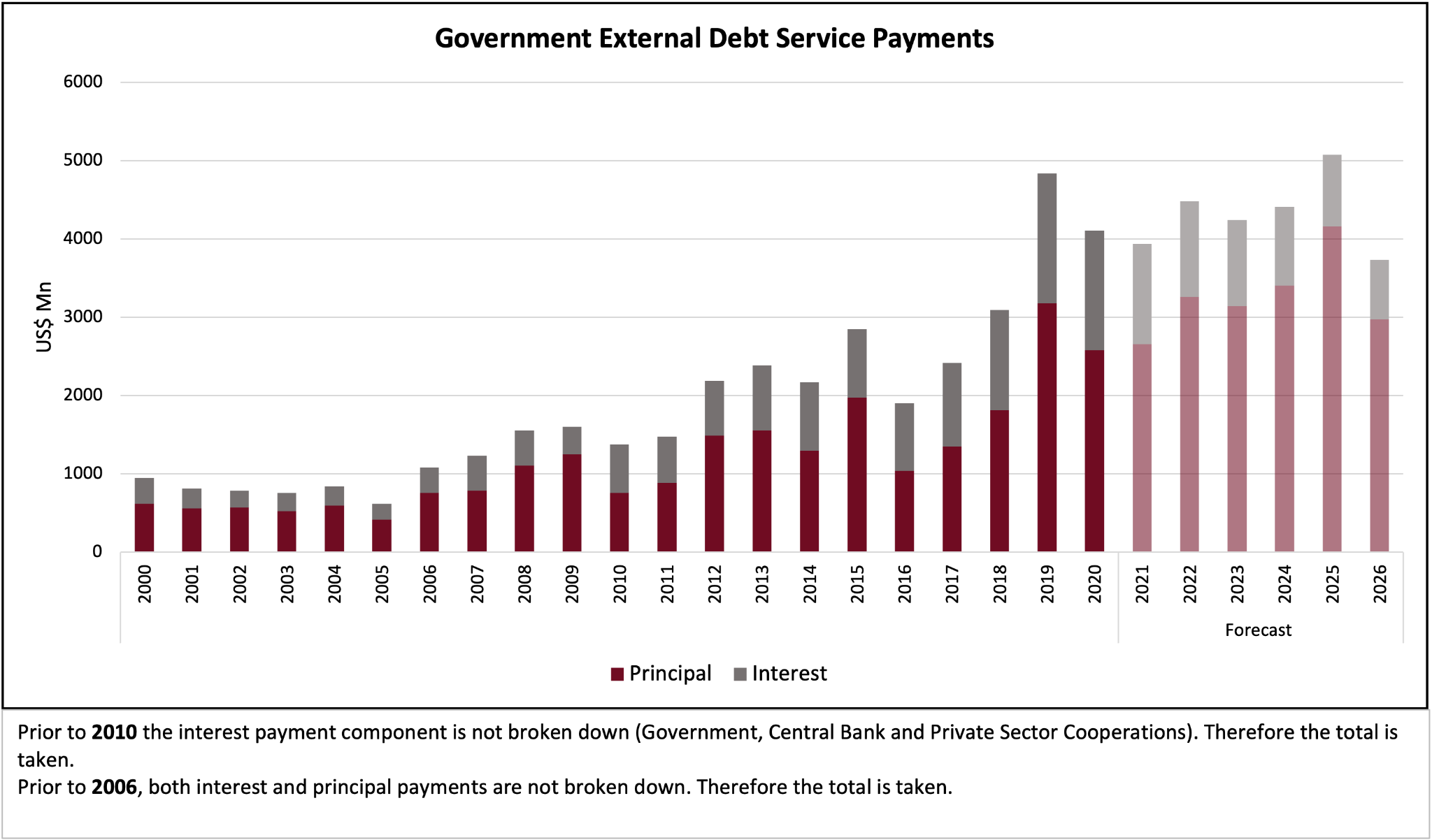

create a balance of payment problem when economic activities and credit picks up. Sri Lanka or any other country cannot live in complete isolation. We have to import some basics such as fossil fuel, pharmaceuticals, and inputs for our exports. Statistics by the Central Bank show that about 80% of our imports are capital and intermediate goods, required for consumption and for our exports. When we print excessive money, that will increase imports and create a balance of payment crisis. In addition, the fall in reserves and the fall in exchange rate will lead to a loss of confidence. Then, foreigners who had loaned money and other investors will take their money back. This is called capital flight. That is one reason the yields of sovereign bonds have increased to very high levels and we cannot issue more sovereign bonds.

But what about rupee debt, you may ask.

One question commonly asked is why Sri Lanka cannot print money if the US and Japan can print money in trillions. This is possible for the US and Japan to some extent because both the US dollar and the Japanese yen are pure floating exchange rates. The US dollar in particular is also used abroad. However, that did not prevent the collapse of the US dollar in 1971 when it was pegged to gold and money was printed in excess.

When the US dollar was a floating currency also it was not immune. After very low rates from 2001, a massive credit bubble was fired in the US and the dollar weakened. Inflation and oil and house prices went up and then collapsed.

Sri Lanka does not have a pure floating currency. Sri Lanka collects reserves through the purchase of dollars and then the sale of dollars to defend the value of the rupee against the US dollar at different rates.

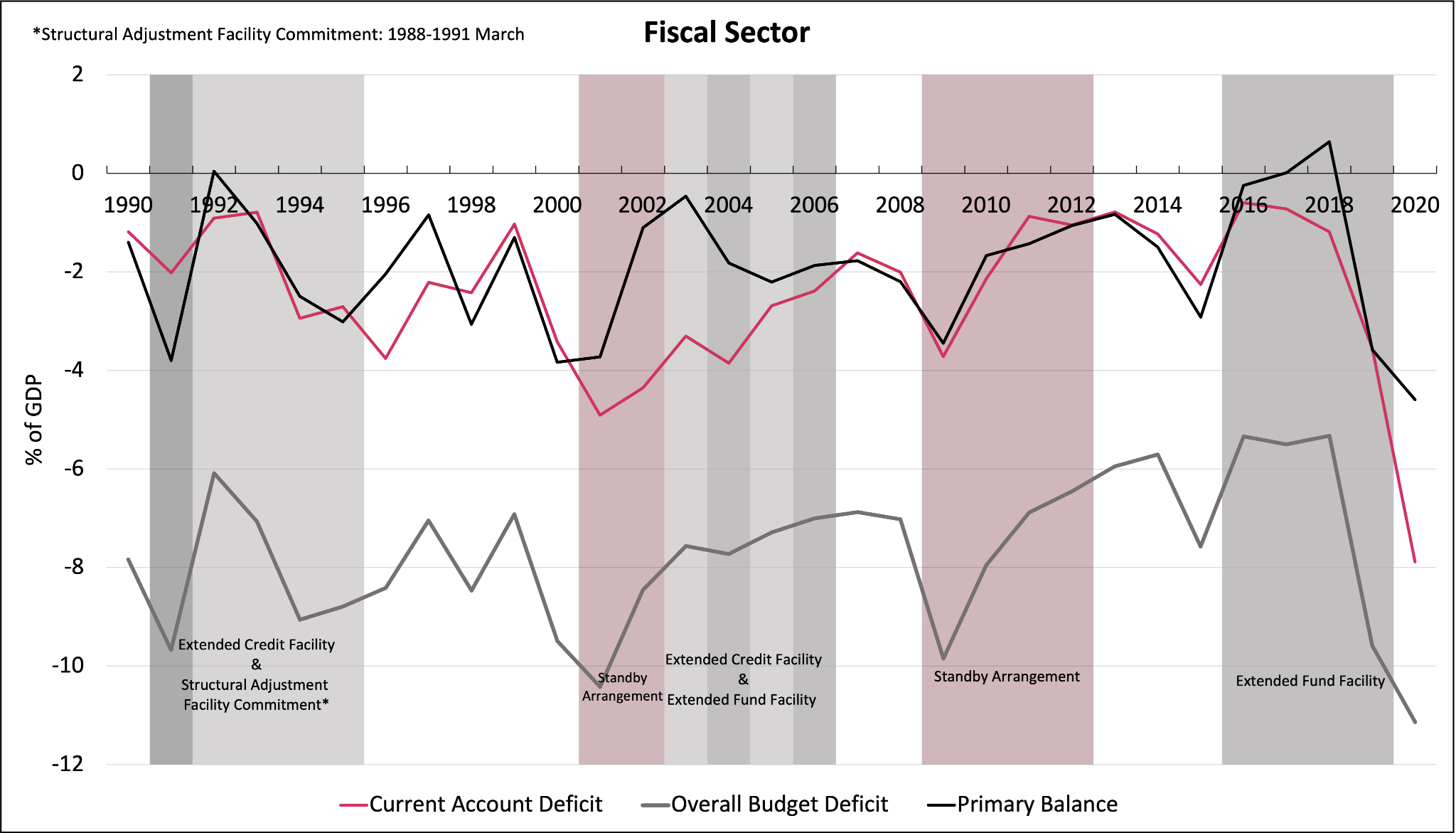

Such countries are much more at risk from printing money than those with a pure floating exchange rate. Consecutive governments of the past resorted to the practice of financing our budget deficit by money printing. One reason Sri Lanka has had to go to the International Monetary Fund many times over the last 70 years is mainly due to such balance of payment crises caused by the excessive printing of money.

Restricting imports reduces the amount of goods and services available in a country and leads to higher prices. When countries without floating exchange rates print money, not just inflation but hyperinflation also can happen.

Zimbabwe created excessive amounts of fiat money that led to inflation rates of more than 1,000% per year. As the currency crashed, notes of million-dollar Zimbabwe banknotes were printed. Eventually people shifted to US dollars. Inflation then stopped. But many were left destitute. Large numbers left as refugees. Creating money without regard to the availability of goods and services can ruin an economy. And worse. It devastates the poor.

It is true that the economy of a country cannot be compared to the economy of a household because people trade in different currencies and trade between countries is a global phenomenon bringing in competitive synergies.

But when money is printed, the main objective of economic policy becomes “saving foreign exchange”.

The MMT advocates of the West did not say to control imports. Some people hold up Japan as an example due to its high debt levels and attempts at trying to ignite inflation there through money printing. But there is no import control in Japan.

So we should not forget that the main objective of an economy and economic policy is not to just have money in every citizen’s hand or saving US dollars to pay our debt. The prime objective of a well-functioning economy is to improve the quality of life of the people and reduce poverty. We can only achieve these objectives by utilising our scarce resources optimally. Hence my teacher’s question, “what if we all have money but not enough goods and services for our consumption?” must be analysed in depth.

Therefore, improving the quality of life, eradication of poverty, and using our resources optimally have to be the broader objectives of the economic policies we implement. This does not mean that we divert from our focus of facing the ever-growing economic challenges before us. However, our solutions to meet short-term economic challenges should not dilute our aspirations or our long-term economic goals of improving quality of life and eradicating poverty.

Monetary history has shown over and over again that the oversupply of money causes inflation and currency depreciation and balance of payments problems. When money printing is continued, it will end in hyperinflation like in Zimbabwe. The poorest sections of the society will be most affected by hyperinflation.

Countries like Venezuela and Zimbabwe are prime examples of the various consequences that can occur as a result of governments running their money printing machines overtime. It results in a situation where they have money, but not the adequate amount to afford their necessities.

What is the solution?

It is understandable that in a global pandemic and a credit collapse some countries printed money, especially when there was no economic activity to make use of the money. But expecting to use it as a permanent solution may cause long-term damage to our economy.

To optimise the use of our resources, we have to remove the structural impediments that stop the people from doing growth-creating economic activity.

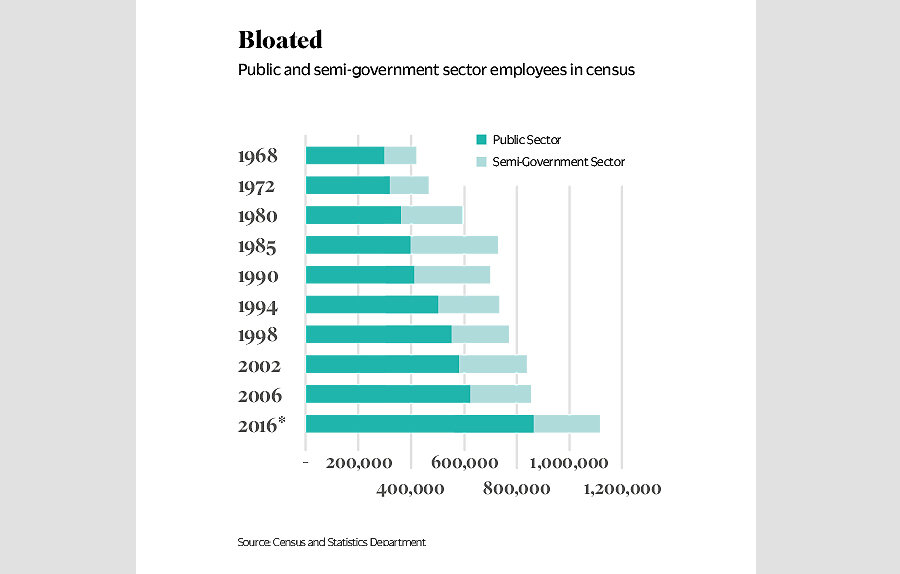

We must restructure our state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and open public sector resources to the private sector, in order to attract money, for example, rather than print money. Ultimately, it is the production of goods and services and getting all Sri Lankans to contribute to economic growth that will help meet our long and short-term economic objectives. Expecting that production will kickstart when excess money is supplied through money printing is surely a not solution. Instead, we should examine the barriers that have to be removed in order to ramp up production. These barriers keep dragging our economy behind.

We should not forget the scenario where everyone was given money through money printing but there were insufficient goods and services to purchase. This lesson taught by my school teacher to my aspirational friend who wanted to lead the country, is a lesson for the whole country. A lesson as to why such thinking is fundamentally flawed.

The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.