By Dhananath Fernando

Originally appeared on the Morning

For the last 76 years, we Sri Lankans have looked at different ways of making Sri Lanka a wealthier and developed country. A popular refrain during every Independence Day celebration week has been that “when we got independence, we were only second to Japan”. Another quote bragged about how good we were, as “Singapore was behind us and they took Sri Lanka as their model for development”.

Unfortunately, much of Sri Lanka’s independence has only been ceremonial, not real. We have still failed to capture the science of equitable wealth creation, which only comes with economic freedom. Economic freedom leads to true and meaningful independence. All countries in the region, including Singapore and Japan, overtook us by establishing the elements of economic freedom at various degrees rather than simply taking Sri Lanka as an example.

Science of wealth creation

Wealth creation is science, not magic. It has always been a function of maximising the use of limited resources and increasing productivity. Both can be done when individuals have better incentives to create wealth. For individuals to create wealth, their rights over property have to be secure. The government should ensure that the property of people belongs to them.

The government should allow individuals to do business and create wealth instead of trying to intervene in markets and pricing. Further, a government poking its fingers in and preferential treatments in a sector serve to discourage individuals from being in the same business.

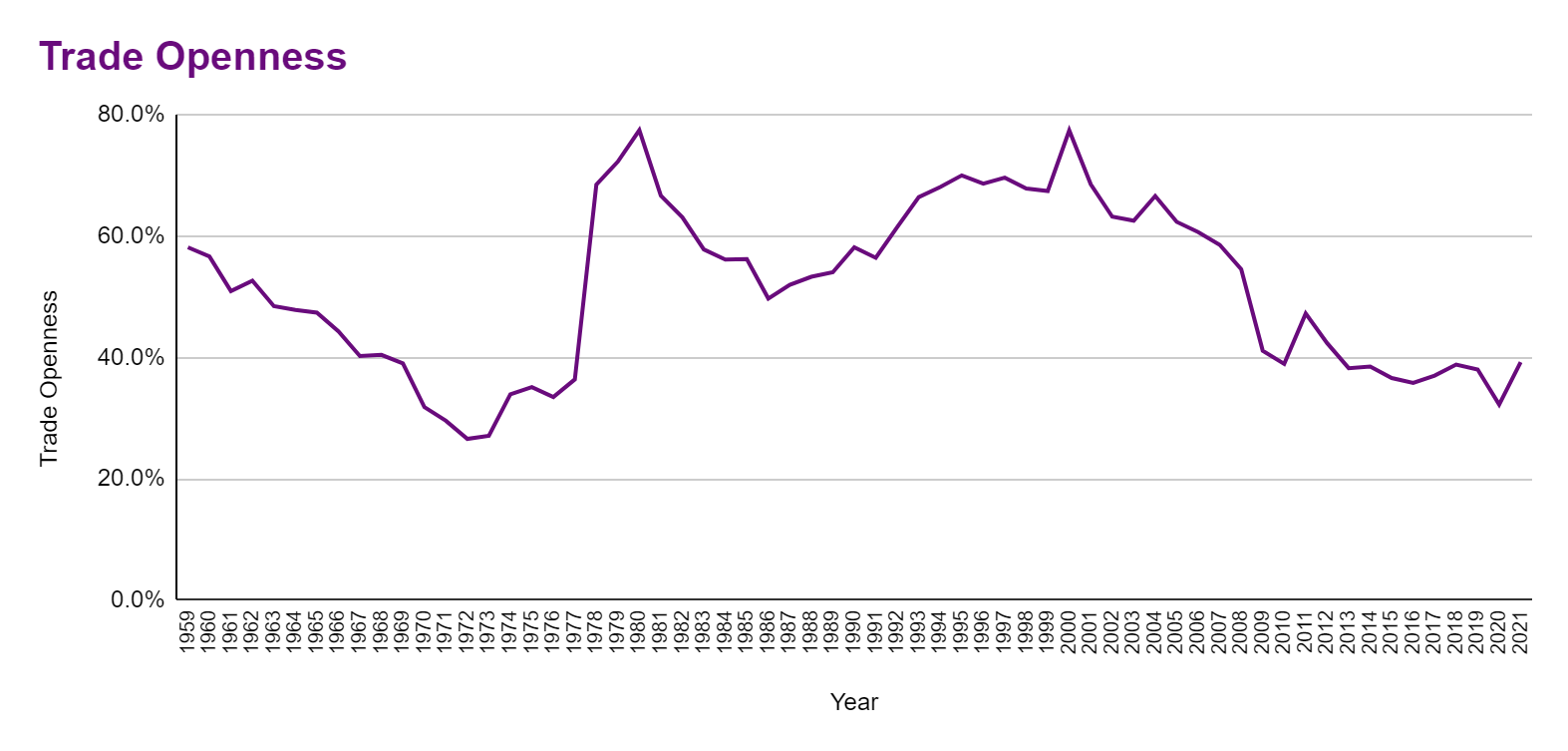

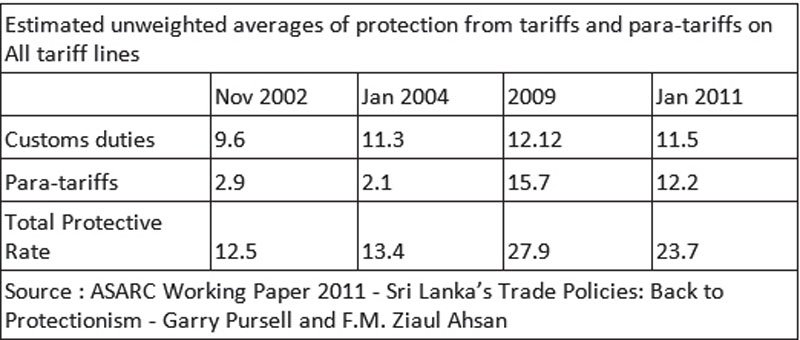

Wealth can also be created when raw materials are competitive in price and good in quality. Having a variety of choices in a competitive market system is paramount. The simplest way of creating a competitive environment is by opening up for international trade.

Regulatory barriers have to be minimal. This does not mean the government plays no part in regulation. The government can adopt a regulatory function without intervening in the market to ensure that the competition and competitive nature of the industries are protected.

Lastly, all transactions in the modern world take place in a fiat currency. Simply put, we store all our production as individuals in a form of a paper called money. The monopoly of money belongs to the government and when it does not protect the value of the money, it amounts to theft of the hard work and production of an individual.

The science of wealth creation is simply establishing these five principles. This has been statistically proven by the Economic Freedom of the World Index by the Fraser Institute.

Over the decades, it has monitored these five indicators and data have shown the relationship and causation between wealth creation.

The per capita GDP of countries with the highest level of economic freedom is on average about $ 48,000 while for countries with the lowest level of economic freedom the per capita GDP averages at $ 6,300.

Even if we consider the standard of living amongst the poorest 10% of the population in the countries with higher economic freedom, the income distribution among the poorest 10% is eight times higher than in countries with very low economic freedom.

Sri Lanka falls under the third quartile, meaning that our performance in economic freedom is not that great. We have ranked 116 out of 165 countries.

Science of economic freedom

In modern times, many people consider happiness as a function of wealth, freedom, and independence. When we look at the data on economic freedom, it is clear that countries with higher ratings indicate a higher score on the UN World Happiness Index as well.

Even if we look at poverty numbers, the countries with higher economic freedom obviously have low poverty rates compared to countries with low economic freedom.

Over the last 76 years, the science of economic freedom is something we have failed to utilise. One reason this column has always advocated for reforms of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) is because a limited government improves the economic freedom of people, which leads to creating wealth. People having ownership and rights over land is another reform we require to improve the property rights indicated in economic freedom, which will also lead the process of wealth creation.

On this independence day, our prime focus has to be on creating wealth. We can create wealth by establishing economic freedom. When we have wealth and economic freedom, we become independent. That is when we leave the trap of poverty, our standards of living improve, and we provide value for the globe.

Happy Independence Day, Sri Lanka.