Originally appeared on Echelon

By Daniel Alphonsus

An unprecedented crisis can only be met with comprehensive and deep reform. Bandages and tinctures will not do.

There are crises and there are crises. But the truly momentous calamities, those that set the stage for the decades that follow are few and far between. Surveying 20th century Sri Lankan history, two such events stand out – the Great Depression and the rice-queues of the 1970s. Those traumatic experiences dictated economy policy for the decades that followed. In the case of the Great Depression, rapid reductions in commodity prices, combined with a global credit crunch, ravaged Sri Lanka’s undiversified plantation economy. A consensus emerged for reducing Sri Lanka’s dependence on international markets.

The Ceylon Banking Commission report of 1934, in many ways the premier pre-independence analysis of Sri Lanka’s economy, observed, “Never before was the vulnerability of the economic structure of Ceylon more forcibly revealed than during this period. The three major products, namely, tea, rubber, and coconut, which between them account for over 90% of the wealth of the country, suffered seriously during the depression. The creed of economic self-sufficiency which became an article of faith in the economic policies of other countries spread to Ceylon as well.” Inspired by war-time planning and the Soviet command economy’s success in industrializing Russia, there was also widespread agreement that in the newly independent third world, governments, not firms, would be the motor of this historic transformation from global dependence to national independence.

Exhilaration soon gave way to enervation. The failure of import-substitution and appalling government record of running enterprises – including the critical plantation sector – paved the way for the open market reforms of 1977. The desperation was palpable. On election platforms, Sirima Bandaranaike accused J.R. Jayawardene of being in bed with the Americans, thinking that would dissuade voters from supporting him. But the ploy boomeranged. Voters, who just two or three decades ago were Asia’s second richest but now had to wait in queues for rice, voted with their stomachs. Their reasoning was simple, if J.R. is in bed with the Americans, then he will be able to secure relief from them.

Despite a quarter-century of the open market model coming to a sudden and unexpected halt in 2004, economically speaking, we are still the children of the 1977 revolution. This year may mark the twilight of that epoch, or at the very least a new chapter.

For Sri Lanka is facing an unprecedented economic crisis. It is a crisis of four tempests, whose sum is a raging storm that threatens to engulf the entire island in its dark thunderous deluge. They are:

Coronavirus: the global and domestic combined supply and demand shocks caused by the Coronavirus.

Original Sin: borrowing liberally from international capital markets in foreign currency, at high-interest rates and with low maturities for low-productivity construction and import consumption.

Negative Growth Shocks: the economic slowdown caused by floods, droughts, the constitutional coup and Easter Bombings.

Stalled Reform: with the exception of the new Inland Revenue Act, the failure to carry through any serious structural reform since 2004 has seen real growth fall.

As a result, we may be on the verge of Sri Lanka’s first sovereign default since Independence. Prior to the pandemic, though the trajectory was grim, there was still hope of avoiding that catastrophe. That hope is now waning fast. The origins of this crisis lie in the early years of this millennium. In 2004, the quarter-century long bipartisan consensus for reform stalled. In many cases – such as tariffs and privatizations – reform reversed. Due to time-lags the reforms of the late 90s and early 2000s continued to bear fruit for some years. But by the turn of the millennium, high-interest dollar debt increasingly became growth’s chief hand-maiden.

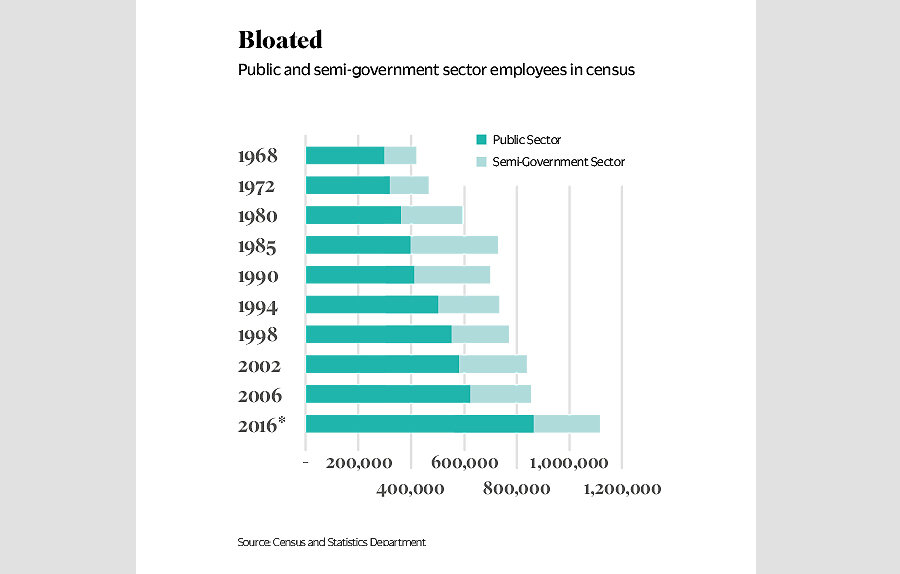

Post-2007 commercial borrowings from international capital markets rose rapidly from almost zero. This fueled a construction and consumption boom soon after the war’s end in 2009. Project loans were spent on empty airports and useless towers. Sovereign Bonds were issued to bridge the government’s ballooning budget deficit; caused by an unprecedently massive and swift expansion of the public sector.

Over the last few years, supported by an IMF programme, the government worked hard to reduce Sri Lanka’s debt-burden and dependence on international capital markets. Sri Lanka ran a non-trivial primary surplus for the first time in 2017, repeating that success in 2018 and upto November 2019 despite the coup and the Easter Bombing. But this alone was not enough.

In reality, the value of public debt rarely declines. What matters is reducing public debt relative to the size of public repayment capacity. In its simplest form, it’s about reducing the value of this equation:

This can be done in two ways. Reducing the value of the numerator, “Public Debt”. Or by increasing the value of the denominator, “Annual GDP”. In the last few years, Sri Lanka adopted a ‘fiscal consolidation’ approach which rightly attacked the numerator. But coalition dynamics and time-lags thwarted progress on the denominator, growth, which is more important. The new government reversed course significantly loosening fiscal policy. It implemented a sweeping range of tax cuts which drastically reduced government revenue. In the language of our equation, these tax-cuts increased the numerator. The wager – to describe the strategy charitably – was that rising public debt would be off-set by an even faster surge in GDP growth, thus reducing the relative value of public debt. That plan has clearly failed. Today, public debt is touching 95% of GDP. The true value, when one calculates all liabilities such as Treasury guarantees for invoices, is likely much higher.

As a result, markets seem to think Sri Lanka is at risk of defaulting for the first time in its history. Bond yields are in the double digits. Among emerging markets, only Argentina, Zambia and Lebanon have higher risk premiums on their debt. A default will be a further blow to an economy that has been ravaged by floods, coups, the Easter Bombings and COVID. The country will be shut off from international capital markets. It will not be able to finance the budget deficit. Inflation unless government spending is cut. Taken together, they could well lead us into an Argentine, Lebanese or Greek-style vicious cycle of default and political instability. An unprecedented crisis can only be met with comprehensive and deep reform. Bandages and tinctures will not do. As Italy has shown neither will attacking the numerator alone: decades of focusing on primary surpluses without structural reforms have only resulted in stagnation. Rather we need the second-round of 1977 type reforms that served Sri Lanka so well. There are many ways of thinking about such a reform programme. However, as the catalyst this time is likely to be a sovereign default, it is easier to label reforms as either an “attack on the numerator” or an “attack on the denominator”.

Attacking the Numerator: Reducing Debt

Reducing public debt – ‘attacking the numerator’ – can be done in three ways. First, increasing taxes. Second, reducing expenditure. Third, selling assets. Sri Lanka will probably have to do all three.

Increasing Taxes: Property Taxes and Tax Loopholes

It is well known that Sri Lanka has one of the lowest tax-to-GDP ratios in the world and has a regressive tax system. This year Sri Lanka’s tax-to-GDP ratio could rank among the lowest 15 countries in the world. However, in the midst of economic contraction raising taxes that reduce consumption and investment could catalyze growth shocks. One solution would be to tax savings, especially those savings that are not productive. The biggest example of such savings is land ownership. A Western Province property tax could raise substantial revenue and encourage efficient use of idle property. In the last decade property prices in Colombo rose by 300%, much of this windfall is the direct result of public infrastructure spending. Our tax system also has many loopholes. Consider the case of excise taxes on cigarettes. Estimates suggest the government could prevent over two hundred billion rupees of revenue leakage over the next decade by introducing a formula for cigarette prices. Similarly, the duty on beedi clearly points to political rather than economic considerations in excise taxation.

Reducing Expenditure: Too Many Men

Sri Lanka has a bloated public sector. From a revenue, productivity and ultimately security viewpoint the large size of the military is a challenge. Around 40% of government salary expenditure is spent on the military. The military, nearing 280 thousand men (compared to the British Army’s approximately 100,000), is holding back our most able men from productive employment. Transferring most of these men to reserves and offering subsidized labour to the export industry through an apprenticeship scheme would substantially improve public finance and propel growth. A similar story of job growth can be found in the public sector.

Selling Assets: Sell Enterprises

The government is poor at managing businesses. State-owned enterprises are renowned for their mismanagement, waste and corruption. The direct cost is colossal. But the indirect costs are even greater. Despite competition from Ports Authority run terminals, SAGT and China Merchant Holdings have played a key role in making Colombo one of the world’s great ports. Imagine if airports and air-services had been similarly open to competition and private enterprise; Sri Lanka could have become an aviation and air-sea hub, as well as a shipping-hub. There are countless other examples throughout our economy.

At this stage of economic development, there is little reason for the state to run enterprises. In fact, the state can increase the value of the assets it owns by selling enterprises without selling land per se. For example, state-owned hotels, container terminals and air terminals could be privatized without selling the land on which they operate. In other words, privatize the enterprises, not their land-holdings. The tax-payer would be significantly better off as the privatization proceeds can be used to settle debt. In addition lease values, for the land, will rise and the land-value will appreciate faster too.

From a productivity point of view, key targets for privatization could be Sri Lankan Airlines, Ratmalana Airport, Jaya Container Terminal and Unity Container Terminal. One simple method of doing this would be to place all SOEs operating in competitive industries in a holding company that has an explicit mandate to sell them within a set time-frame, failing which they are automatically listed on the Colombo Stock Exchange.

Attacking the Denominator: Productivity Growth

There is only one tried and tested way of going from third world to first in the space of a few decades: manufacturing exports. Sri Lanka successfully completed the first step of this process by the 1980s when it established apparel exports industry, which remains Sri Lanka’s only manufacturing export. In 1983, Sri Lanka was about to move up the value chain to semi-conductors, which would have led to South-East Asian and East Asian style growth. But Black July was engineered, and the semiconductor plants being built in Katunayake by Motorola and Harris Corporation were shipped-off to Penang. Similarly, we missed the wave of Japanese investment that was about to begin at that time.

Since then Sri Lanka hasn’t developed a major manufactured export. The challenge for Sri Lanka is to create new higher-productivity export industries. This is a complex task requiring government effort. But Sri Lanka has done it before. The tested strategy of the 1977 revolution is as follows. First, create investment zones where the usual constraints affecting investment can be managed. That is the genius of the Free Trade Zones. Second, make Sri Lanka’s exports competitive: reduce tariffs (a tax on imports is a tax on exports) and sign Free-Trade Agreements. Third, enable efficient factor allocation: remove regulatory constraints on agricultural production and update labour laws. Fourth, unleash the power of the developmental state by fast-tracking the MCC grant, designing clever export subsidies and most importantly completing land reform.

Investment Oases

The engines of Sri Lanka’s manufacturing exports are the Free Trade Zones. It is here that the apparel industry started. It is also the zones that were the cradle for the island’s solid-tyre export industry and they remain the primary site of all other manufactured exports. The reason for this is that zones make it much easier for an investor to open a factory. Land, electricity and water are available; regulatory permissions are already secured; customs officers and other government agencies are on hand. Over time an eco-system of trained labour and ancillary suppliers also develops. Despite being near capacity, Sri Lanka failed to build any new free trade zones between 2002 and 2017. So its no surprise to hear investors complain that access to land is the primary constraint for investment.

Almost all of Sri Lanka’s Free Trade Zones are managed by the BOI. One exception is the DFCC Bank run Linden Industrial Zone. The BOI run model worked well and was competitive in the 1980s. Today the world has moved on. In order to attract new investors in sectors outside apparel, Sri Lanka needs to allow international zone operators. For example, Sri Lanka should court a Chinese free trade zone operator, a Japanese free trade zone operator and a Singaporean one to establish facilities in Sri Lanka. These zone operators will then leverage the relationships they have with manufacturers in their countries and regions, doing the job successive governments have failed to do since the late 1980s.

The energies of Sri Lanka’s own private sector could also be unleashed in zone-management. MAS and Brandix run successful textile parks in Sri Lanka and India. There is no reason they couldn’t successfully run a zone in Sri Lanka. The failure is not the central government’s alone. As far as I know, no other province has done what the Wayamba Provincial Council did within a couple of years of the formation of a provincial government: establish not one but two province run industrial zones, at Heraliyawala and Dangaspitiya respectively. The Northern Province with its devolutionary fervour, combined with access to the KKS Port and Palaly Airport, should be particularly ashamed.

A pilot project could deploy under-utilized state land around Ratmalana to create an electronics free-trade zone. There is no better place in Sri Lanka due to proximity to a port, railway and airport, universities and technical schools and trained labour.

Export Competitiveness

But no one will build factories in Sri Lanka if input costs are high. In this era of global supply chains, one country rarely adds more than 20% to 30% of a product’s final value. Therefore, being able to import components and raw materials at the same prices as in competitor countries is vital. However, Sri Lanka has some of the highest effective tariff rates in the world. To make matters worse they are highly complex, creating ample room for discretion and thus delays and corruption. If Sri Lanka is to become the trading and manufacturing hub of the Indian Ocean, it will have to benchmark its tariffs against Dubai and Singapore. This is not new to Sri Lanka. In 1994 it has a simple three-band tariff structure. It is only after 2004 that Sri Lanka’s effective tariff rate sky-rocketed, primarily due to the cascading effects of CESS and PAL. Their abolition would be a very good start.

Similarly, during the 1977-2004 Sri Lanka’s real effective exchange rate was kept more or less constant. A weaker currency makes foreign goods dearer domestically and makes Sri Lankan goods cheaper on global markets. This helped ensure the competitiveness of exports and acted as an automatic, non-discretionary import substitution incentive. However, from 2004 onward the real effective exchange rate started creeping upwards, discouraging exports and encouraging imports. By 2017 Sri Lanka’s real effective exchange rate was 31% higher than in 2004.

Finally, Sri Lanka’s competitiveness is eroding because all its competitors are signing free trade agreements (FTAs). Sri Lanka must fast-track deeper goods and service trade integration with India, China and ASEAN. Most importantly, we need to become part of the two-major trade agreements the CPP11 and the RCEP. The constraints of space and time, robbed of the opportunity to discuss the importance of a new Customs Act, the implementation of the National Export Strategy or other reforms to facilitate cross-border trade. Suffice to say they too are essential.

Efficient Factor Allocation

Land, labour, capital; it is the development and allocation of these factors that determines the wealth of nations. Sri Lanka’s capital allocation is relatively efficient. Our challenge today is to ensure the efficient allocation of land and labour.

Land

Many cite East Asia’s successful land reform as the key to their economic prosperity. Studwell’s How Asia Works is perhaps the most persuasive and readable account. There is much to commend in this analysis. Granting freehold land to families already farming it will increase agricultural productivity. This is true of Sri Lanka too. One critical land reform, that can be implemented quickly, will be to make small-holders of the existing tea-estate workers. This will improve productivity, as the principal-agent problem will be solved. In addition, with freehold rights, they will have every incentive to replant and improve the land. Access to credit will not be an issue; the land itself will act as collateral.

As for the RPCs, the factories and land equal to the value of their remaining leaseterm can be transferred to them freehold. They can then offer extension services and an out-grower model to the new small-holders. In a similar vein, there is absolutely no good reason for the continuation of the Paddy Lands Act, especially in the wet-zone. In fact, some of the land in the wet-zone restricted by the Paddy Lands Act was never paddy land in the first place. This law is a major barrier to more productive use of land for high-value export crops, such as spices.

Having got land out of the way, we can move on to labour. Sri Lanka’s labour laws have created a de facto caste system of a few highly protected insiders and a sea of completely unprotected informal workers. In fact, the failure to make labour law more flexible is an important reason why over a million Sri Lankans work in the hazardous conditions of the Gulf. It is better to have some protection for many, than a great deal of protection for a few. Especially as labour law is a major constraint to growth. The downsides of more flexible labour laws can be effectively managed through a targeted social security net, such as in the Danish Flexisecurity model, which combines high levels of labour market flexibility with generous social safety nets, such as solid unemployment insurance.

The Developmental State

Finally, Sri Lanka needs to restructure its state to facilitate rather than hamper development. The first is a question of a simply accepting reality. What credibility does a country have when it refuses the largest grant in its history (MCC), while going-cap in hand asking for debt moratoria from its creditors?

Second, the state-owned enterprises in natural monopoly sectors, such as railways and power-lines need to be depoliticized and forced to be efficient. Depoliticization can be significantly achieved by simply passing a new law. The law can require that the appointment of directors of all State-Owned Enterprises be subject to the approval of a Constitutional Council appointed nominating board, with clear ‘fit-and-proper’ criteria. A similar mechanism is already in place for banks.

Furthermore, efficiency can be improved by introducing competition, resolving conflicts-of-interest and raising transparency. Sri Lanka’s competition law does not cover state-owned-enterprises: this allows public sector monopolies to enjoy rents at the expense of citizens. That needs to go. It is also absurd, for example, that the Sri Lanka Ports Authority is owner, operator and regulator of port terminals. The public sector is rife with such conflicts-of-interest which appear designed to breed corruption and mismanagement.

These are the key changes, but information matters too. As they are owned by the tax-payer, SOEs should have greater disclosure requirements than firms listed on the Colombo Stock Exchange. But a start would be to simply require SOEs to follow all CSE disclosure requirements, this can be done by law or by requiring SOEs to list their debt on the CSE. Or both.

There are also government departments that need to be made into SOEs. The railways are the most important example. If the railways were able to borrow money, which they could if they were an SOE, they could then finance the electrification and double-tracking through the development of land the CGR owns around railway stations.

Way Forward

The real economic policy statements in Sri Lanka are not budgets but IMF programmes. Budgets are often nothing more than promises of bread and the certainty of circuses. They bear little reality to actual revenue and expenditure, much the less actual economic management. As such the crescendo of this crisis, and thus opportunity, will be the inevitable IMF programme. It is almost certain that Sri Lanka will enter into its 17th IMF programme later this year or early in 2021. Sri Lanka has been in IMF devil-dances for much of its post-independence history. We have failed to undertake the reforms needed to grow and to protect our sovereignty. The IMF kapuralas have also failed to require front-loading reforms: allowing Sri Lanka to get away with cosmetic compliance rather than really restructuring the economy.

With COVID, the IMF is also overextended; perversely this improves its bargaining position. As a result, this programme can be a water-shed that combines both fiscal consolidation and export-driven productivity growth. It must be a landmark programme with a single objective: to be the last programme the IMF has with Sri Lanka. Then, as in 1977, Sri Lanka may just pull-off a Phoenix-like rise from the ashes. If not, then the demons of hunger, unemployment and debt-collectors will follow.

(Daniel Alphonsus was an advisor at Sri Lanka’s Finance Ministry. He also worked at Sri Lanka’s Foreign Ministry and at Verite Research. Daniel read philosophy, politics and economics at Balliol College, Oxford and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School where he was a Fulbright Scholar.)