In this weekly column on The Sunday Morning Business titled “The Coordination Problem”, the scholars and fellows associated with Advocata attempt to explore issues around economics, public policy, the institutions that govern them and their impact on our lives and society.

Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

Beginning with our education system, when a student successfully completes their Ordinary Level they are segregated into Commerce, Arts and the ones with the best results choose Maths or BioScience. A completely new direction from the humble times of the O/L. A student at the end of their studies in their chosen field can become a great medical practitioner, a legal profession, or even an engineer. But during their time at university or as a matter of fact in school their basic knowledge in economics, such as what drives inflation, interest rates, why am I getting less dollars than last year at the money changer, is at the mercy of a silver tongue politician, a master of selling excuses. The excuses which are hastily gulped by you, the ordinary citizen. The current economic situation created by Covid-19 is a sterling example of this disconnect. Many well-educated citizens who haven’t studied rudimentary economics during their learning years join the workforce in obedience. What you don’t know won’t hurt you. Sometimes even those who studied economics have forgotten that ‘Economics’ is the social science of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. We all often miss the common sense that we have to make a continuous effort on making our choices with limited resources available and organise and coordinate to achieve maximum output by increasing productivity. Ultimately economics is about you. In this case “ability to test” at present is our limited and most scarce resource. How we utilise it to the greatest effect is probably the decision-maker on how fast we can overcome and how to minimise its impact on the wallet of each Sri Lankan. Undoubtedly “testing” in isolation will not work without the policies of social distancing and medical policy management. Economics, medicine, bioscience, technology or anything is no longer isolated. There is always an economic angle. We have to find the winning formula to come out of COVID-19.

Economics of testing strategy

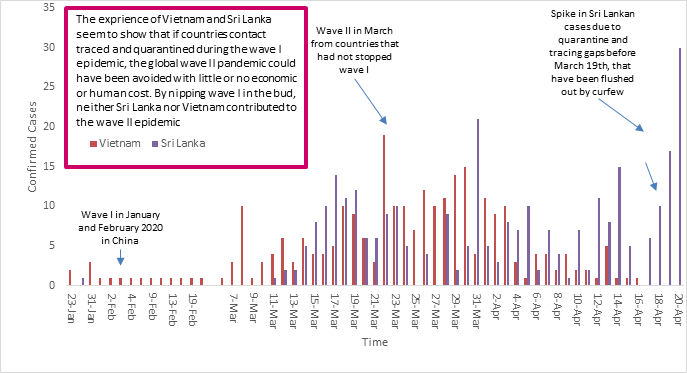

The countries who faced the pandemic successfully have one thing in common. Their testing strategy and coordination between policies has been incredible. New-Zealand, Vietnam, South Korea, Taiwan the unsung hero and even China have given absolute priority to testing. Ability to test has been discussed on various platforms in Sri Lanka. But still, the public seems to run on an attitude “This shall be passed”. Some tend to think opening up is the end of this battle, without weighing the pros and cons to the economy. Let’s face the grim reality we are not a rich country and the world doesn't want our currency, hence running the press in perpetuity is not a solution, it’s the opposite of it. Hence, the only viable economic option is to be at the helm of the new normal and “testing” will determine the shape of the new normal. Sri Lanka did a commendable job in combating the wave 1. (Wave 1 is infected cases directly from China). We had a very successful quarantine process and all index cases (cases, where the person got infected, is traceable) at the beginning was identified and did not provide any space to progress onto community transmission (infected cases from small clusters of the population). In contrast, some developed countries like Italy and the USA were hit immediately with community transmission right from wave 1.

However, Sri Lanka has seen a sudden uptick in cases as a result of coordination issues between our social distancing policy and a few vital loopholes in our testing policy. At the beginning, the testing capacity was about 100 and to increase that limit to 1,000 we took a considerable amount of time. Testing even at this juncture is a limited resource, so we have to maximise the productivity on testing. We have to maximise resources to increase testing capacity, while also ensuring that we test the right samples while overall testing numbers are increased. That is where exactly we slipped (Advocata highlighted the loophole in the testing policy)

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (Accessed on 1st of May 2020)

Basic visual diagram to understand the initial testing strategy by the author

We took a fairly long time to increase the testing as it is yet not up to a reasonable level. We did not utilise the private sector from the get-go, even though it has critical capacity for lab tests in the island. Additional lapses in testing the forces who are a high-risk segment (as they manage the isolation on the frontlines) caused a sudden increase in infections. According to medical experts’ opinion COVID-19, some infected cases indicate symptoms (symptomatic cases) while there are many cases that don't indicate symptoms (asymptotic cases). However, they both are the carriers of the virus. On our testing strategy, since testing capacity is limited, we have to provide priority for individuals who are symptomatic and who have been contacted with a previously identified patient. In economics, we had the opportunity cost of not testing asymptomatic cases at the beginning. It is not that simple; there are some high-risk groups who arrived from overseas and some asymptomatic cases in quarantine centres. So maximising the limited resource “testing” became very complicated. We did not expect a member in the triforce to get infected and the possibility of their high-frequency commuting carrying the virus across domestic borders. Some of them having gone on leave to take a break after the yeoman service they delivered have now become part of the problem by increasing the probability of more cases in low-risk areas. Countries like Vietnam identified this loophole early and they conducted frequent tests among high-risk groups. Drivers, cleaning staff at hospitals and often committing all individuals all fall into high-risk categories.

Economics on increasing testing capacity

One main delay to increase the testing capacity was lack of engaging the private sector on testing at the beginning of the pandemic. Private sector labs are mainly run by major hospital groups that are well regulated by the Ministry of Health and have the critical capacity to get the numbers in. A PCR test is a confirmatory test (Symptoms have to be indicated and a doctor has to recommend the test) and an individual cannot get it as a screening test (a test to identify an infection/ disease). As a result, private hospitals can only conduct PCR tests for the in-house admitted patients only. Of course, the cost of the private sector tests will be higher but by restricting private sector to conduct the tests as a laboratory test and imposing price controls on the tests is a sure way of discouraging the ability to increase the testing capacity from volunteer testing. The outcome would be someone who could afford a test at a higher price will now utilise the state health apparatus, adding further strain on limited resources. At the same time price controls will discourage the private sector to invest and further expand testing capacity. In an ideal case scenario, the private sector has to be encouraged to conduct the tests out of hospital premises to reduce the degree of transmission of the disease.

Given community infections being reported we can’t adhere to our previous testing priority strategy as now the asymptotic cases have been reported and the opportunity of voluntary testing has to be opened up. The cost of an economy that is idle is not bearable for a developing country like Sri Lanka.

Solution

The only solution lies in improving our testing strategy and increasing capacity. There were some locally made PCR tests reported which is commendable and we should encourage them to upscale it to a commercial level. However, introducing a commercial scale medical equipment takes time as the process needs extensive testing is needed for approvals to ensure accuracy and reliability of the tests. Increasing testing by using basic economics on what is available and more feasible. Having fewer regulations on the private sector on testing, while we maintain free testing conducted by the government is the first most economically feasible option. Engaging the private sector will save an opportunity cost of testing more cases in the government healthcare for people who can’t afford it. As community infections have been reported now voluntary testing ability is a must. Only the private sector is likely to bring the investment for advanced and convenient testing like drive through tests, and mass-scale testing needed for industry. To coexist with Covid-19 till the boffins at labs to come up with a vaccine is still in the distant horizon, hence increasing tests is the only way out to defeat the invisible enemy at the moment.

The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.