Originally appeared on Daily FT, Economy Next

By Nishtha Chadha

This year’s International Women’s Day theme is #EachforEqual - a concept grounded in the idea of ‘Collective Individualism’. Collective Individualism is the idea that each of us is part of one whole. Our individual actions, conversations, behaviours and mindsets go beyond the confines of our individual lives, and can have a significant impact on our larger society. Collectively, we have the capacity to create a gender equal world.

Gender equality in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka still has a significant way to go when it comes to gender equality. The Global Gender Gap Report 2020 ranks Sri Lanka 102 out of 153 countries in the gender equality index. Women’s economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment and political empowerment are major areas of concern, and only seem to be getting worse.

In 2006, Sri Lanka ranked 13th on the same gender gap index. In other words, over the last 14 years, the country has dropped 89 places on the index. Today, women are twice as likely as men to be unemployed, and barely 9% of Sri Lankan firms have women in top managerial positions. Only 5% of Sri Lanka’s parliament is made up of female representatives.

Gender equality is not just a women’s issue, but a business issue. The World Bank Vice President for South Asia Region, Hartwig Schafer, has stated that Sri Lanka specifically could grow its economy by as much as 20 percent in the long-run by closing its gender gap in the workforce. Increasing women’s labour force participation can improve productivity by not only adding more people to the workforce, but also by enhancing diversity of thought in the workplace.

So, why aren’t Sri Lankan women achieving their full potential?

A recent publication by the World Bank ‘Getting to Work : Unlocking Women’s Potential in Sri Lanka’s Labor Force (Vol. 2)’, cites that cultural norms continue to be a pervasive barrier to increasing women’s labour force participation in Sri Lanka. Entrenched with gender stereotypes, these cultural norms have direct implications on women’s educational pursuits, career longevity, and ability to participate in decision-making roles. What’s important to understand about cultural norms, however, is that they do not exist in a vacuum. Gender stereotypes which limit a woman’s ability to access education and economic opportunities.

One example of these discriminatory policies are the exorbitant taxes on menstrual hygiene products in Sri Lanka. Access to safe and affordable menstrual hygiene products remains somewhat of a luxury for many Sri Lankan women. A leading contributor to the unaffordability of these products in Sri Lanka, is the taxes levied on imported items.

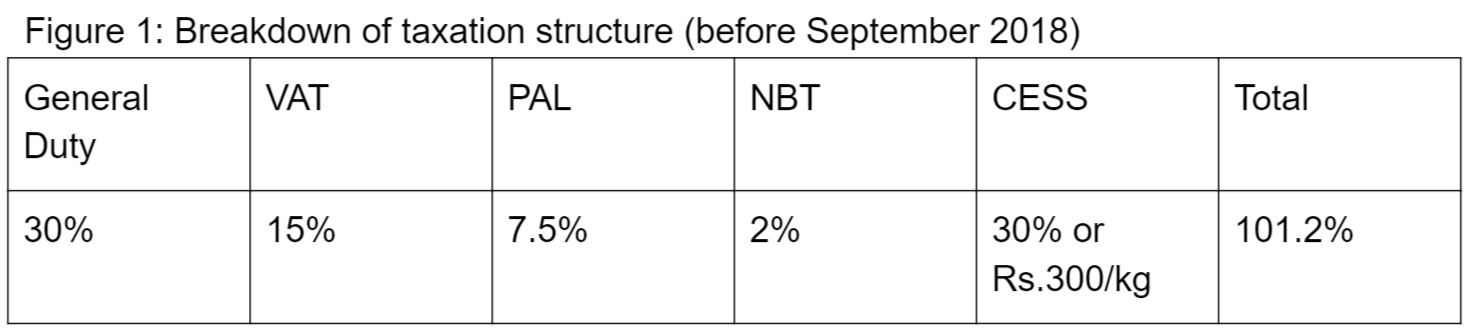

Sanitary napkins and tampons are taxed under the HS code 96190010 and the import tariff levied on these products is 52%. Until September 2018, the tax on sanitary napkins was 101.2%. The components of this structure were Gen Duty (30%) + VAT (15%) + PAL (7.5%) + NBT (2%) and CESS (30% or Rs.300/kg). In September 2018, following social media outrage against the exorbitant tax, the CESS component of this tax was repealed by the Minister of Finance. Yet, despite the removal of the CESS levy, sanitary napkins and tampons continue to remain unaffordable and out of reach for the vast majority of Sri Lankan women.

The average woman has her period for around 5 days and will use 4 pads a day. Under the previous taxation scheme, this would cost her LKR 520 a month. The estimated average monthly household income of the households in the poorest 20% in Sri Lanka is LKR 14,840. To these households, the monthly cost of menstrual hygiene products would therefore make up 3.5% of their expenses. In comparison, the percentage of expenditure of this income category on clothing is around 4.4%.

The impact of unaffordability

The high cost of menstrual hygiene products in Sri Lanka has direct implications on girls’ education, health and employment.

According to a 2015 analysis of 720 adolescent girls and 282 female teachers in Kalutara district, 60% of parents refuse to send their girls to school during periods of menstruation. Moreover, in a survey of adolescent Sri Lankan girls, slightly more than a third claimed to miss school because of menstruation. When asked to explain why, 68% to 81% cited pain and physical discomfort and 23% to 40% cited fear of staining clothes.

Inaccessibility of menstrual hygiene products also results in the use of makeshift, unhygienic replacements, which have direct implications on menstrual hygiene management (MHM). Poor MHM can result in serious reproductive tract infections. A study on cervical cancer risk factors in India, has found a direct link between the use of cloth during menstruation (a common substitute for sanitary napkins) and the development of cervical cancer; the second-most common type of cancer among Sri Lankan women today.

The unaffordability of menstrual hygiene products is proven to have direct consequences on women’s participation in the labor force. A study on apparel sector workers in Bangladesh found that providing subsidized menstrual hygiene products resulted in a drop in absenteeism of female workers and an increase in overall productivity.

Slashing taxes for gender equality

Internationally, repeals on menstrual hygiene product taxation are becoming increasingly common due to their proliferation of gender inequality and the resulting unaffordability of essential care items, commonly known as ‘period poverty’. Kenya was the first country to abolish sales tax for menstrual products in 2004 and countries including Australia, Canada, India, Ireland and Malaysia have all followed suit in recent years.

If Sri Lankans are serious about creating an equal platform for women and girls to achieve their full potential, ‘Collective Individualism’ is certainly the key. Gender equality can no longer be just a ‘women’s issue’. It’s an ‘everyone issue’. Each and every Sri Lankan has a responsibility to demand real action from their policymakers, to promote gender-sensitive policies and abolish taxes like this, which actively limit a woman’s ability to achieve her full potential.

By reducing the rates of taxation, the cost of importing sanitary napkins and tampons will simultaneously decrease and stimulate competition in the industry, further driving prices down and encouraging innovation. The conventional argument in favour of import tariffs is the protection of the local industry. However, in Sri Lanka, sanitary napkin exports only contribute a mere Rs. 25.16 million, or 0.001%, to total exports.

Increased market competition would also incentivise local manufacturers to innovate better quality products and ensure their prices remain competitive for consumers. Other common concerns pertaining to the issue of low quality products potentially flooding the Sri Lankan market if taxation is reduced are unlikely to materialise, since quality standards are already imposed by the Sri Lankan government on imported products under SLS 111.

If menstrual hygiene products are made more affordable it is likely that more Sri Lankan women will be able to uptake their use, allowing them to attend more school days, work more consistently and, by extension, access more opportunities. Moreover, with more products entering the market, women will have expanded consumer agency, allowing them to purchase products that address their specific needs without being economically burdened for it. This would remove a significant barrier to women's empowerment and create a wide-scale positive impact on closing Sri Lanka’s present gender gap.

Gender equality can only be achieved when we begin dismantling the structures that disadvantage our most vulnerable counterparts. Abolishing Sri Lanka’s menstrual tax may just be one small step towards achieving this. The Advocata Institute has launched an online campaign titled ‘the costs of being a woman’, which highlights taxes that disproportionately affect women. With every discriminatory tax and policy that is abolished, the collective impact could be transformative.

That is what #EachforEqual is about - sharing the responsibility to create a more equal world for each and every one of us.