Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

The gentleman who cleans and repairs my roof every month is the breadwinner of a family of four, and a father to two children who are still schooling. He earns a living working for a company for an end-of-the-month salary, but it is paid based only on his working days. I often ask him: “How is life?” He always grins and provides me with the same answer: “On payday Rs. 5,000 is worth just Rs. 50. One week before payday, Rs.50 is worth Rs. 5,000.”

I recalled what he said when recently, a Minister stated in Parliament that “the Rs. 5,000 was given for a month, not to be spent within a week”. Things took an emotional turn following this statement and social media castigated him for being tone-deaf and being detached from ground realities.

This makes complete sense from the receiver’s point of view. Rs. 5,000 is not adequate for a family of four! A simple calculation breaks it down as follows: Rs. 1,250 per person per month, which means about Rs. 42 per person a day, and about Rs. 14 per meal, even if the calculation is based on the rather broader and irrational assumption that the money is only spent on food.

According to the Household Income and Expenditure Survey by the Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka’s mean household expenditure per month is Rs. 54,000. In the estate sector, which is in the lowest part of the income pyramid, it is about Rs. 34,000. On average in Sri Lanka, food expenditure is Rs. 19,140 per month and even in the estate sector, it is at Rs. 16,890. This is according to data for the year 2016. Bearing this in mind, if we add 5% inflation every year, the expenditure must be significantly higher today.

It is painfully obvious that an allowance of Rs. 5,000 is not at all adequate for a month’s expenditure. However, in defence of the Government, it was communicated that the Rs. 5,000 was not a stipend and is adequate for a month as a supplement for people whose livelihoods are affected. The Government reiterated that this was a form of financial assistance to help them keep their nose afloat in these trying times. It is no secret that the Government is running a massive budget deficit to the extent of 8.9% of GDP in 2021. Therefore, providing Rs.5,000 is also a challenging task, given the strained and limited financial resources.

This points to just one conclusion; that nobody but poverty is to be blamed for the current circumstances. Sadly, as a country, we are in denial of this fact.

Let’s look one step further. Our inability to tackle poverty is our own doing. We have failed over and over again, from one successive government to another, to set our fundamentals in the right direction. Unfortunately, we still continue to drift ignorantly in the same wrong direction.

Sri Lanka’s workforce is highly state-dependent and the island’s massive inclination towards a welfare state is far beyond our affordability or financial capacity. Politicians promise long lists of free supplies from fertiliser to sanitary napkins and to even jobs in the government sector. It is a vicious cycle of politicians cheating people and people cheating themselves, owing to their enormous reliance on the State. This unsustainable codependency has today shoved the island to one of its worst economic calamities since independence.

Starvation-driven crowds protest in the streets of Colombo requesting for more money. The Government is struggling to make repayments to our external creditors; $ 4 billion on average over the next four years. Our reserves stand at $ 5 billion in total with the Government still running a significant trade deficit.

Why is the cost of living high?

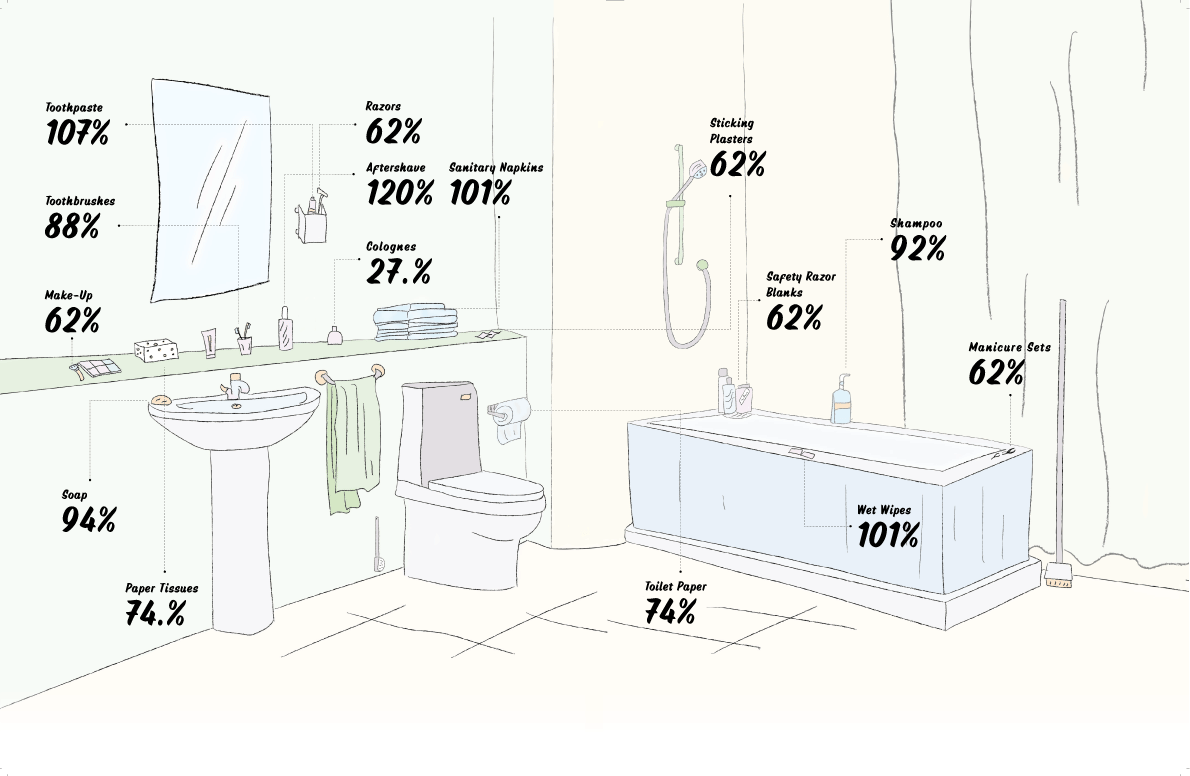

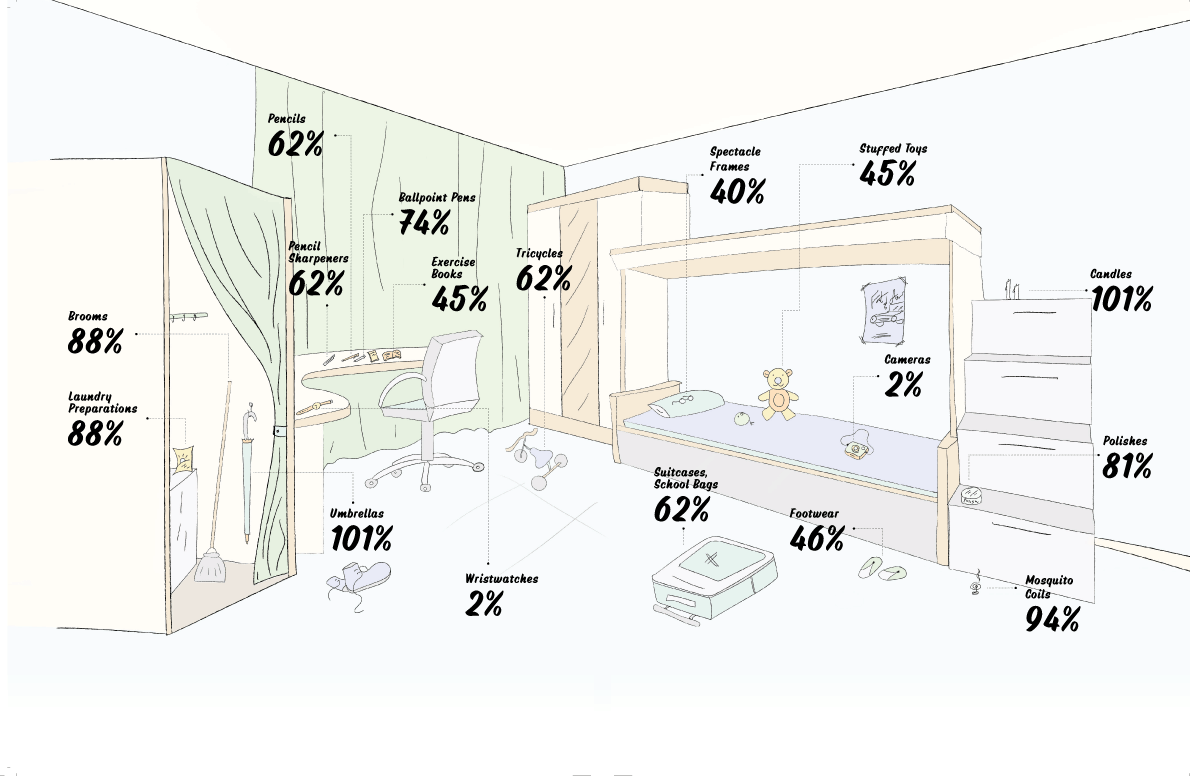

Our cost of living has always been a much-discussed topic over the decades. The real reason why it’s high is because we are very unproductive as a country. Despite low labour costs, our production tends to be expensive and unproductive. We spend about 20-50% more than the average price on some essential goods. In certain product categories, it goes beyond 100%, which is almost double. Our products are not competitive on a global scale. Consecutive governments have failed at making reforms that are required to make them competitive. Our tax structure is 80% indirect tax and 20% direct tax, where most of the basics, including food items, are subjected to a tariff. That is one reason why most of the gazette notifications which are released are on tariff revisions. When this happens, every government becomes the victim of their own policies when the cost of living starts rising.

We often look at increasing local production but fail to consider improving local manufacturing and competitiveness. Global benchmarks are forgotten. We continue to ignore the consumer. As a result, higher incomes become meaningless in Sri Lanka as our quality of life continues to deteriorate. For example, even if you have a vehicle, it is difficult to commute and if you are in business, there are way too many interventions and bureaucracy. If you use the courts as a means of conflict resolution, the matter takes decades to be resolved. Thus, we don’t really meet the basic requirements for a satisfying quality of life or ease of doing business.

Solution

There is only one solution – hard reforms to make Sri Lanka’s products competitive. We can make products competitive through competition. We can compete and be competitive only if we increase productivity. Darwin’s theory of evolution that only the fittest survive is still very much valid. The problem is that we have failed to grasp the reality that we must evolve with the changing times.

If we continue to disregard the need to evolve our fate, it will be catastrophic and a payday where we feel that Rs. 5,000 is actually worth Rs. 5,000 will be a distant dream. If the hard reforms are not prioritised and pushed through, all Sri Lankans will live forever in that week before payday, just like that nice gentleman who cleans and repairs my roof.

The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.