In this weekly column on The Sunday Morning Business titled “The Coordination Problem”, the scholars and fellows associated with Advocata attempt to explore issues around economics, public policy, the institutions that govern them and their impact on our lives and society.

Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dilshani N. Ranawaka

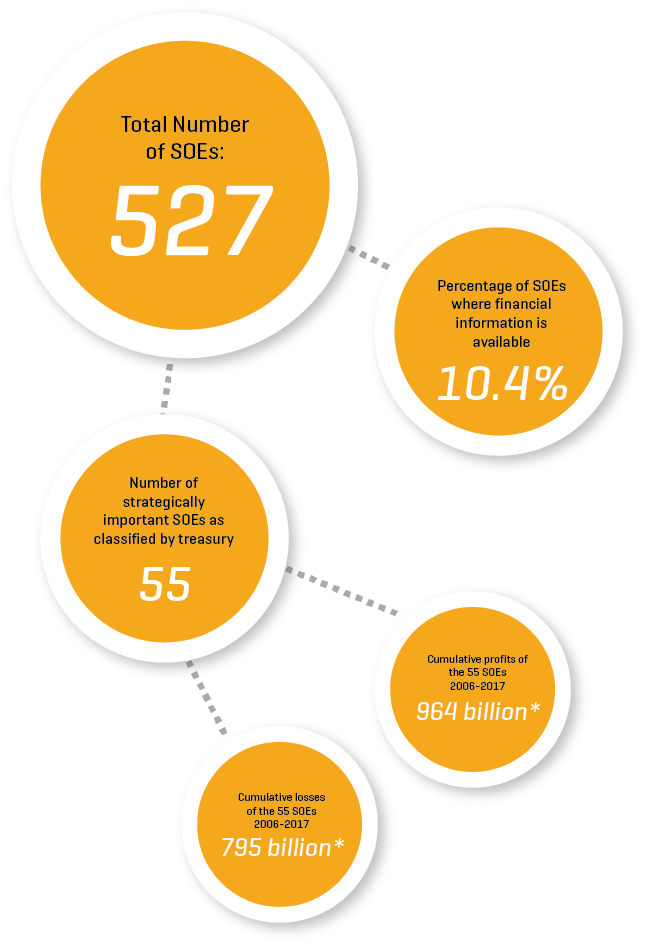

Is the Government aware it has gazetted 527 SOEs?

Unveiling an invisibility cloak of the state was the first task I did as a fresh graduate. Behind 55 strategic State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) identified by the Ministry of Finance (MoF) lies another 450+ SOEs making their contribution to the “Coordination Problem”.

Even at face value, it seems unlikely that a small country like Sri Lanka needs the government to run a pool of SOEs as large as this. Interestingly, the MoF doesn’t have a count of all its SOEs, with the Annual Report only mentioning that there are 400+ SOEs. However, there are at least 527 SOEs, subsidiaries and sub-subsidiaries gazetted. To be specific, the 527 SOEs can be broken down to 424 principals, 84 subsidiaries and 19 sub-subsidiaries.

Of the 400+ SOEs that the government is aware of, the Department of Public Enterprises tracks the profits and losses of only 55 SOEs, which they have identified as ‘strategic’.

This raises two questions.

Why doesn’t the government know the number of enterprises it runs? Anyone running a business should at the very least know the number of organisations it is in charge of.

Why does the MoF only track 55 SOEs? What are the losses that come from the remaining 450?

Let’s take the Ministry of Power and Energy and Business Development for example. The ministry’s losses add up to a cumulative net-loss of Rs. 363,945Mn during the past 11 years. The ministry governs 4 principal SOEs, 6 subsidiary SOEs and 12 sub-subsidiary SOEs adding upto a total of 22 bodies.

When one further explores these subsidiaries, it is quite logical to ponder the rationale for these categorizations. For instance; the Ceylon Electricity Board has two subsidiaries under it. The first subsidiary Lanka Electricity Company (LECO) has three sub-subsidiaries LTL Transformers, LTL Energy, and LTL Galvanizers. The second subsidiary LTL Holdings (Pvt.) has another sub-subsidiary LTL Energy (Pvt.). Is it any wonder that we have erratic power supply? A convenient way to track all these entities would be to establish all of them under one subsidiary; LTL Holdings.

It is time we question the logic of establishing so many SOEs, given that their profits and losses are not tracked, and a majority do not even publish annual reports. When the losses incurred by these entities are added to the equation, it is clear that there is large-scale mismanagement taking place.

The multiple layers of incorporation (principal, subsidiary and subsidiary bodies) enhances the divisibility of responsibilities. Furthermore, the problem with having too many entities makes it hard for them to be monitored. Since SOEs are governed by the state, the debt burden is weighed heavily on the government and then transferred to the taxpayer.

Moving beyond the profits and losses of these enterprises, an equally shocking fact is that out of the 527 SOEs that have been gazetted to date, information of their purpose (classification as commercial and non-commercial entities) of 284 SOEs is not freely available, and cannot be found from government sources.

Can these 527 enterprises be utilized or do a majority need to be shut down because of their losses? The government cannot afford to keep bailing out its mismanaged enterprises - the fiscal space simply does not exist.

The first step to addressing the problem of SOEs, is to figure out the number of entities the state governs. A bi-annual census of SOE conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics, with detailed reports (a current requirement fulfilled only by 55 SOEs) on every SOE is a must. It is only from here, when the government has an idea of the extent of the problem that we can move into questions of improving accountability and introducing better governance structures.

The question remains, when the government is unaware of the number of entities it is responsible for, why should citizens pay for their loss making, inefficient, institutional excess?

Sri Lanka has a total of 527 State Owned Enterprises out of which regular information is available for only 55. The inefficiencies and mismanagement which riddle our SOEs are explored in the Advocata Institute's new report “State of State Enterprises in Sri Lanka- 2019". To read more on SOEs and download full report visit www.advocata.org.

Dilshani Ranawaka is a Research Executive at the Advocata Institute whose main research areas are public finance, behavioural economics and labour economics. She can be contacted at dilshani@advocata.org or @dilshani_n on Twitter.